Avure basket to chamber

It's hard to pin down exactly when high-pressure processing (HPP) for food graduated from a novel technology two decades ago to the mainstream status it now enjoys. But with a global annual growth rate of nearly 25 percent, it's clear that food manufacturers have embraced HPP as another viable method of serving up to consumers safe, tasty products—from salsa and guacamole to lunchmeat and juices and more.

In 2011, approximately 260,000 tons of refrigerated foods and beverages were treated with high pressure worldwide, according to internal research from leading HPP machinery manufacturer Avure Technologies. These numbers, based on new machine liters sold worldwide and shifts per week, are closely matched by another major HPP player. Hiperbaric estimates that more than 300,000 tons were processed in 2011, not including lab machines, and that the global market of machine capacity will be near 8,000 liters by the end of 2012.

At a time when consumers are focused on health and food safety, HPP delivers a fresh, savory product with reduced or no chemical preservatives—as well as without the sodium those additives may contain. Performed after primary packaging, HPP kills bacteria in the food or drink by literally squeezing pathogens such as listeria, E.coli and salmonella to death while safeguarding the product's nutrients, texture and flavor. Water under high pressure—typically 87,000 pounds per square inch—is distributed evenly and simultaneously on all sides of a product to burst the bugs without smashing the package.

Garden Fresh Salsa

This cold pasteurization step, especially suitable for heat-sensitive products, improves product quality (there's no degradation due to high heat) and significantly extends shelf life. Jack Aronson, founder, president and chief recipe developer at Garden Fresh Gourmet, says HPP is a "game changer," providing a 70-day shelf life for its all-natural spinach dip instead of the typical seven days-a tenfold improvement. This benefit has enabled the Michigan-based company to distribute its fresh products overseas, into Europe and even South Korea.

Aronson says Garden Fresh Gourmet was one of the first privately held companies in America to install an HPP system, which it did about six years ago. It now owns two model 350L horizontal systems from Avure to process all its natural products, except for a few high-pH salsas. "It's expensive. It adds about 15 to 20 cents a pound," Aronson admits. "But we're not a commodity item. We sell high-quality salsas and dips. It's worked out perfect for us."

Currently, the majority of Garden Fresh Gourmet's 100-plus products are preservative free. Aronson says, "Eventually everything we do is going to be all-natural, and HPP is a big part of that."

PACKAGING REQUIREMENTS

Like any post-packaging process, HPP places certain demands on the materials. And the technology has its limitations: Products must contain enough moisture to transmit the pressure throughout, and as little air and/or headspace as possible—vacuum-packed products are ideal. But HPP can accommodate a range of formats, including bottles, jars, trays and flexible packs. As long as the package can flex about 15 percent on any one surface, it will withstand HPP compression.

Since packages will be immersed in water, graphics need to be water friendly. Garden Fresh Gourmet, for example, applies vinyl labels to its 48-oz jar of Jack's Special Salsa, which "hold up terrific under HPP," Aronson says, although he adds that sometimes labeling is done after HPP instead of before.

HPP requires packages to have a hermetic seal-a bonus is that any leakers will be obvious when packs exit the system. According to Errol Raghubeer, vp, microbiology at Avure, sometimes the size of the sealing area may need to be increased and experience has shown that a flat, straight seal holds up better than, say, a diamond-shaped seal.

Garden Fresh Salsa did extensive tests to make sure its packaging materials worked and seals held up during HPP yet were easy for consumers to peel off. "For all these films to perform and still be consumer friendly, we invested over $600,000 in losses and breaches. It was worth it—but it wasn't easy. In our company, we never do what is easiest. We do what is best. That's a pain sometimes, but that's our motto."

When it comes to the package's barrier properties, there are a couple different thoughts. If a company opts for HPP for food safety reasons and extended shelf life is a happy by-product, it might be able to switch to lower-barrier materials that are more cost-effective, especially for fast-selling items. However, the consensus leans more toward protecting the shelf life with high-barrier materials. "You don't want packaging to be the weak link in the chain," Raghubeer cautions.

Hormel Natural Choice

Hormel Foods, which began using HPP in 2003 for some meat products, specifies high-barrier structures for its HPP applications, which include its Natural Choice deli meats line. Daniel Hirst, manager of packaging development at Hormel Foods, says, "We could opt for lower-performing films, but this would simply compromise our shelf life and defeat one of the key benefits of HPP."

Phillip Minerich, vp of research and development at Hormel Foods, agrees. "The extended shelf life of the product requires more attention to the packaging systems to protect the quality attributes of the product throughout its microbial shelf-life," Minerich says. "The packaging systems are now required to manage moisture, gas and light transmission over an extended period, which typically has taken us down a path of using higher barrier materials."

Involved parties expect to concentrate more on packaging during the next stage of HPP development. "We're spending more time now on package material issues than on microbial issues," Raghubeer says, adding that a number of suppliers are working on developing films specifically for HPP, although he wasn't able to share any details because of confidentiality agreements.

Multivac HPP

Package designs can be optimized for HPP. Packaging machinery manufacturer Multivac provides HPP system solutions through a partnership with Uhde High Pressure Technologies, a German machinery manufacturer of high-pressure vessels. Cem Yildirim, Multivac's sales manager of Systems and Automation Group U.S., says one of the company's areas of expertise is understanding how a package's geometry will react in HPP. Multivac, with its experience in upstream food packaging (such as thermoform/fill/seal operations), can help engineer the package/process for success, including integrating the batch HPP process into automated packaging lines. "We look at it holistically," Yildirim says. "This has got to work together if it's going to work at all."

OWN OR CONTRACT OUT?

Nearly all food processors overseas opt to buy their own HPP systems. But here in the U.S., where a number of service companies (aka toll processors) provide HPP on a contract basis, about 80 percent of food companies do high-pressure processing in-house. And a number of those companies sell their excess line capacity to non-competitors.

Major toll processors in the U.S. include American Pasteurization Co. (APC), AmeriQual Foods, Global Leading Foods USA, HPP Food Services, Millard Refrigerated Services, Safe Pac Pasteurization LLC and Universal Pasteurization Co. They also offer various post-HPP services, such as label application, coding, package inspection, secondary packaging and shipping.

In May 2012, APC announced a partnership with The National Food Lab (The NFL) to expand its services on the front end. It is now able to offer testing for food safety/quality and validation all the way through HPP implementation, which APC vp Greg Zaja says results in faster time-to-market. A new two-liter unit for high-pressure testing will be available at the lab in fall 2012. Additionally, APC clients now have access to The National Food Lab's suite of services, including challenge studies, commercialization, product development, sensory services, shelf-life studies and consumer research.

According to Jaime Nicolás-Correa, director and global commercial manager at Hiperbaric USA, "Service providers are increasing because of the high demand for HPP technology by companies that either don't have the space to implement HPP technology or don't want to invest in capital expenditures."

Some food companies start with a service provider. "Then, if it works, they invest in their own machine," Nicolás-Correa says. Despite what could be a fast return on investment depending on volumes and throughputs, entry-level commerical HPP systems can cost from $1 to $2 million.

In addition to the initial machinery cost, plant improvements might be required, which could add to the financial outlay. For example, some of the larger systems available weigh upwards of 50 to 70 metric tons and may require floors to be reinforced.

FresherTech Quattro

A new player in the North American market, FresherTech promotes its systems as significantly lighter weight compared to competitors. The weight savings is due to laminated steel frames and how the pressure chambers are made. While Avure, Hiperbaric and Multivac systems are wire-wound designs (wire is wound around the outside of the chamber tens of thousands times to contain the pressure), FresherTech uses auto-frettage—a technique used for HPP food applications until wire winding supplanted it in the early 2000s—yet modifies it slightly in a final proprietary process. The resulting pressure vessel is about half the weight of competitive systems producing the same output, making it less costly to ship and easier to move for installation, but without compromising any strength, according to FresherTech.

Other plant requirements are compressed air to operate the machine, electricity (systems draw a lot of power to reach pressure so check the specs) and water. The water is mostly recirculated, but about 15 percent of water can be lost in the process. Nicolás-Correa explains that during decompression, as water quickly leaves the system, friction causes the water to heat up a bit and companies may opt not to pay to cool it for reuse.

NEW HPP TECHNOLOGIES

Advancements in HPP continue in several areas, but primarily around shelf-stable foods, modified-atmosphere packaging (MAP) and higher throughput.

• Shelf-stable foods: Because HPP kills bacteria but not the spores, applications so far have been for refrigerated foods and beverages. However, researchers are working to adapt the technology for shelf-stable items to significantly improve food quality.

Since 2005, a consortium of food and packaging scientists from the U.S. Army Natick Labs, major food producers, Avure and the Institute for Food Safety and Health (previously the National Center for Food Safety and Technology) has been focused on combining pressure with heat to sterilize rather than pasteurize low-acid foods. Natick wants to improve the quality of military Meals-Ready to Eat (MREs) to boost the troop's nutritional intake and morale.

The pressure-assisted thermal sterilization (PATS) process preheats the food and then applies high pressure (120,000 psi in this case). The pressure further raises product temperature to achieve sterilization—that is, to kill the spores as well as the pathogens. The sterilization temperature (121-deg C) is held throughout the pressure process, which is less than five minutes. Once the pressure releases, the food returns to the original preheated temperature. As a result, thermal degradation is reduced, producing higher quality products than traditional retorted foods. (PATS is undergoing a name change to temperature-assisted pressure sterilization or TAPS.)

In February 2009, the Food and Drug Administration approved high-pressure sterilized mashed potatoes in an MRE pouch. In application, though, pouch delamination has been an issue. According to Avure's Raghubeer, the research team now includes a packaging materials company to address this and other potential obstacles.

Adding low heat with pressure may also improve the taste of fresh pasteurized foods. Researchers at Oregon State University have found that pressure mitigates the product damage heat causes during processing. In tests on fresh milk, they were able to preserve the taste and extend the shelf life from 15 to 20 days using traditional heat pasteurization to 45 days using heat with pressure.

Also developed in 2009, Hiperbaric's 55HT system combines pressure (about 100,000 psi) and temperature (5 to 90 deg C) for pasteurization applications.

• MAP: Many foods use modified-atmosphere packaging to extend shelf life by replacing oxygen with other gases. Because HPP itself creates a longer shelf life, MAP may or may not be necessary. Multivac's Yildirim explains, "All packs let gas back in after a time. That's what you have to pay attention to. If you have a product that will be on the shelf for six months, you would want to limit the oxygen transmission rate for that time." Depending on the product, MAP might also still be needed to protect against rancidity, off-flavors or discoloring due to oxidation.

HPP systems are designed to release the pressure and drain water as quickly as possible to optimize cycle times. Raghubeer points out that one issue with the HPP/MAP combination is the formation of white spots or other damage to the product due to the compression and decompression of gases in the package. Controlled or slowed decompression following HPP solves the product damage issue, but also results in longer cycle times and slower production rates.

"Although Avure owns the patent for slow/controlled decompression, we recommend the alternative of reformulating the gas components on the MAP," Raghubeer says. "This avoids the issue of product damage and white spots formation, without any decrease in productivity."

Multivac handles MAP applications with staged decompression and has applied for a patent. Tobias Richter, product manager in the Systems Business Group and responsible for high pressure equipment at Multivac, says, "With the help of so-called ‘holding torque,' we create short rest periods in which the polymer can regenerate. In this way, the packaging material is stressed considerably less and retains its functionality even after the high-pressure treatment."

• Higher throughput: The faster the process, the more cost-effective it is. Manufacturers continuously work to boost overall throughput.

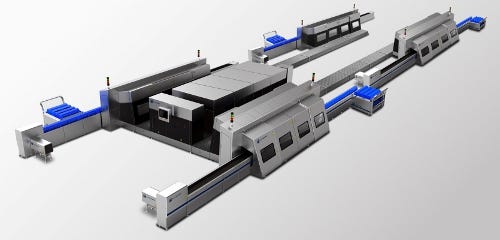

Hiperbaric HPP system

Hiperbaric's 420L system has a 380mm diameter vessel—the largest single machine in the market—and is able to process about 4,500 lbs of product per hour. The 420L is also an integrated version, meaning the unit's intensifier pump is positioned above on a mezzanine rather than alongside to save floor space.

Multivac offers a Tandem 700L unit, which is two 350L systems that share a bank of intensifiers so the pump is working all the time. While cycling on one side, processors can use the other side to clear and/or load other baskets. The Tandem system processes more than 5,000L per hour. Because it has half the number of intensifiers as two single systems working side by side, the company says it's less expensive and easier to maintain.

FresherTech touts fast basket loading and unloading, with custom baskets designed for specific products. According to the company's website, "Rather than careful placement in the basket by a trained crew member, the package is merely dropped into the slot in the basket. Because loading/unloading is a significant percentage of the cycle time, this results in noticeable increases in throughput." Custom baskets also make it easier to automate the loading and unloading.

These are the high points about HPP and its implications for packaging materials and operations. For a list of links to more details and videos about HPP, visit www.packagingdigest.com/MoreHPP.

American Pasteurization Co. (APC), 414-453-7522. www.pressurefresh.com

AmeriQual Foods, 812-867-1444. www.ameriqual.com

Avure Technologies, 615-224-2600. www.avure.com

FresherTech North America, 707-299-6258. www.freshertechusa.com

Global Leading Foods USA, 512-517-1366. www.glfoodsusa.com

Hiperbaric USA, 305-639-9770. www.hiperbaric.com

HPP Food Services, 310-830-8020. www.hppfs.com

Millard Refrigerated Services, 402-896-6600. www.millardref.com

Multivac, 816-891-0555. www.multivac-group.com

Safe Pac Pasteurization LLC, 267-324-5631. www.safepac.biz

The National Food Lab, 925-828-1440. www.thenfl.com

Universal Pasteurization Co., 402-474-9500. www.universalcoldstorage.con/hpp.html

How HPP works

Packages are loaded into cylindrical baskets, which carry the product into the pressure vessel. The chamber is sealed and water is quickly pumped into it, at low pressure. Then an intensifier pump fills all the voids with water. The water is compressed and held for the necessary period of time, usually between three and five minutes. The system is decompressed, releasing the pressure and the water, which is drained and recirculated. Baskets exit and packages are unloaded, either manually or automatically.

.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like