March 11, 2015

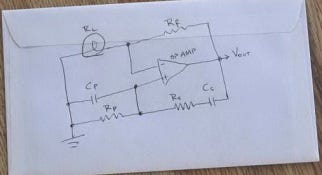

Wein bridge oscillator schematic

In a real sense, automation is like surgery. It can be life saving for the patient, but unnecessary surgery is one of the most horrible things you can do to a person. At best, surgery is expensive, painful, and a lot of work. The poor patient always faces a painful recovery period during which they don't function at their best. At worst, things can go disasterously wrong.The same goes for automation. In fact, everything I've said about surgery can be said about automation with only minor wording changes: It's expensive, painful, and a lot of work. The poor folks who live through an automation project always face a protracted recovery period in which things generally don't go right, and the system doesn't function at its best.

You use the three Ds of robotics (ergo, automation) to decide when it's worthwhile to fool around with automating a task in the first place.

All automation tasks start out as manual tasks. If you don't learn to do it manually, first, then you've a snowball's chance in Hell of automating it successfully.

So, you start with the task being done manually, then review the manual operation to see if it fits any of the three Ds: dull, dirty, or dangerous. If you get a hit on any one of those characteristics, it's a candidate for automation. If not, forget it.

Most often, the characteristic that points to automating a task is "dull." Most of the things people do around factories very quickly degenerate into "dull." That's why factory automation is such a big business.

You may be wondering why I chose to slap up a Wein bridge oscillator schematic as an image for this posting. It's because a Wein bridge oscillator taught me the value of automation in the first place. Specifically, it taught me the value of automated data logging.

In the early 1970s, I was playing around with a capacitive plasma probe. The stupid thing was supposed to measure the dielectric constant of partially ionized gas at the edge of a glowing ball of plasma. The probe entered the schematic as the capacitance labelled CP. The thing consisted of a couple of pieces of wire mesh forming plates of the capacitor, with the partially ionized gas floating in between. The measurable capacitance depended on the gas's dielectric constant.

Before I could pronounce the thing ready for prime time experimentation, though, I had to trace the CP vs. frequency curve of the oscillator experimentally. I knew what the plasma sheath's dielectric constant was supposed to be, and what that should translate to in terms of probe capacitance, and what that, in turn, should lead to in terms of oscillator frequency, but nobody was going to believe it until I experimentally verified the frequency/capacitance curve.

The worst part was measuring its stability.

This was before the days of computerized datalogging systems, at least for undergraduate Physics majors. So, I had to do it manually. Six hours of sitting at a work bench with a stopwatch staring at a digital frequency-counter display. The only movement was in the last two digits of the display. Every thirty seconds, I had to write down the value displayed in those two digits. Since the time between readings was so short, I couldn't multitask with anything else to relieve the tedium.

Talk about mind-numbingly DULL!

Fast forward thirty years to when I was mapping the characteristic of an angle-of-attack probe in a wind tunnel. After exactly one session taking the data down manually, I spent a month or so building a motorized system to automatically log hundreds of data points. A data run took about fifteen minutes, so every fifteen minutes the computer would set off an alarm at the end of a run. I'd then take about thirty seconds to reset the system for the next run, then go back to reading my novel.

The datalogging was still dull, but I didn't have to do it. The automated system did it. I read a novel.

C.G Masi

C.G. Masi has been blogging about technology and society since 2006. In a career spanning more than a quarter century, he has written more than 400 articles for scholarly and technical journals, and six novels dealing with automation's place in technically advanced society. For more information, visit www.cgmasi.com.

.

.

You May Also Like