Most manufacturing operations have a graveyard of unused equipment. Those machines come in handy, though, when a plant has to cobble together a packaging line either in a hurry or on a budget, or both. Here are five tips to remember when faced with a challenging packaging line assembly project, from veteran engineer John R. Henry.

Known as the Changeover Wizard, Henry is the owner of Changeover.com, a consulting firm that helps companies find and fix the causes of inefficiencies in their packaging operations. He has, literally, written the book on packaging machinery and is the face and personality behind packaging detective KC Boxbottom, the main character in popular articles on PackagingDigest.com.

On June 12, Henry spoke about assembling packaging lines with available machines at the new Packaging Education Hub at EastPack 2018. First, he reminded us that nimbleness in production is all-important for strategic success, which gives us two great reasons to consider using idle packaging equipment:

You do not have time to wait for new machinery.

You do not have the money to risk for capital expenditures. After all, 75% of new products fail.

“Franken-lines are not only something you’re going to have to do, but you need to embrace them because it gives you the opportunity for strategic success,” Henry says.

To help track your existing packaging machines, he recommends you develop a database of all equipment in the company that identifies:

• The type of equipment (such as filler, case packer or palletizer);

• The make, model, serial number and year built;

• The condition—you’ll need to know how much work, if any, will be needed before the machine can operate efficiently and if that work can be done in-house, by the manufacturer (if it is still in business) or by a refurbishing/engineering firm;

• The capacity, such as what products it can handle (liquid, powder and such), the expected operating speed, and what packages and sizes it can accommodate;

• The location—you’ll need to know where the machine is stored, especially if you have an extensive warehouse or more than one plant;

• Its availability—note if the system is currently in use, reserved or available/idle.

With this information collected, you’re in much better shape to start your packaging line assembly process.

Here are Henry’s five tips on how to put together a packaging line from your company’s unused but available equipment:

1. Determine requirements

“The best surprise on a packaging line is no surprise,” Henry says. “The way you avoid surprises is by asking questions. But if you don’t ask the right questions, you won’t get the right answers.”

Henry suggests asking questions and getting answers about what is needed from three angles: product, facility and regulatory.

• On the product side, you’ll need to know how many products you need to make—your capacity requirements—and then work towards from there to determine how fast the packaging line needs to operate to produce that capacity.

Remember to ask when you’ll need the capacity, too. “If you’re making ice cream, you probably need a lot of capacity from May through September,” Henry says. “Not so much October through April.”

Put together a complete Bill of Materials (BOM) for the product and a complete BOM for all package components. And get actual samples as early as possible. You need actual samples because there are no “standard” products that are “just like…” something else.

Or if you can’t get samples, get prototypes. 3D printing technology for additive manufacturing can help and is always advancing. “You can buy a 3D printer from Amazon for $200,” Henry says. “There’s no excuse for not having an additive printer in every department in the plant. They are very easy to use; they are no harder to use than any other printer.”

• From a facility point of view, once you know where the line will be placed in your plant, get all the pertinent measurements, including the length, width and the floor-to-ceiling dimension—which Henry emphasizes is not the same as the ceiling height. “We got fooled one time because we knew the ceiling height, but the floor turned out to be elevated a foot and we had a real problem with the height of a machine,” Henry remembers.

Make a note of any interferences—such as doors and columns—as well as floor loading necessities, that could limit access to the packaging line or impair its operation.

Check the utilities. Do you have the right setups for electric, pneumatic air, cooling water or washdown water? Are there any special construction considerations because of the industry, such as foods, chemicals or pharmaceuticals?

• Regarding regulatory requirements, you’ll need to find out what the requirements are for internal and external customers. Some will be governmental, from governing agencies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and whoever manages building codes in the specific country.

Some will be non-governmental standards. For example: “The sprinkler system…is not regulated by any government agency. It’s regulated by the National Fire Protection Assn. (NFPA), which is a private, non-profit conglomerate of insurance companies,” Henry says.

Other needs will be from industry standards bodies, such as 3-A Sanitary Standards for dairy, Intl. Organization for Standardization (ISO) and ASTM Intl.

Your company may have policies and practices you need to adhere to, such as Zero Access for machine safety. Plus, your customers might require you adhere to their policies and practices.

Lastly, find out if there are any other industry practices that might apply.

NEXT: Develop a plan

2. Develop a plan

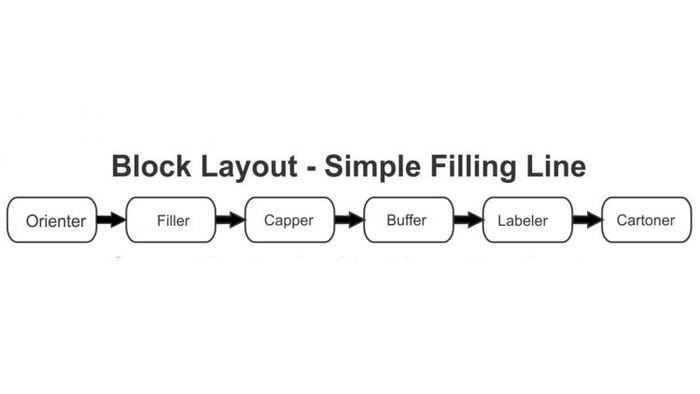

Before you can develop your plan, identify all steps in the packaging process. A simple block layout is fine to indicate the machines you will need. “This is not necessarily how the line will be laid out,” Henry says. “There is no scale or anything. All we’re trying to do here is show the major pieces of equipment that we’re going to need for this project.”

Source: Packaging Machinery Handbook

Once you’ve itemized the equipment, you can guesstimate a cost range. If this is outside the cost that Marketing estimated for the product, “you may just have saved yourself a whole lot of work,” Henry says, “in developing a line that is economically outside of consideration.”

Selecting the machine types is an iterative process. “There are 20 different types of fillers, for example,” Henry says. “Gear, piston, gravity, overflow and so on. What type do you need for your product?”

Fine tune what kind of machines you need, how fast they needs to go, how big they’re going to be and what level of automation you need—from some manual operations to semi-automatic to fully automatic. This may be determined by the available existing machines, or it may be determined by the skill level and pool of operators and mechanics.

You should still write specifications and expectations for the line’s output. This includes the integration strategy: How will you tie all the machines together into a smooth-running line?

Finish the budget and do a timeline.

Then STOP. “Take a deep breath,” Henry recommends. “Get everyone to agree to the plan. Get it in writing. And get people to actually sign a document that says this is what the plan is.

“Now, the plan is going to change…but at least you’ve got agreement on where you’re starting from.”

NEXT: Select the machines

3. Select the machinery

You’ll need to personally and visibly inspect the machinery to determine if it is a fit. Find out when the system was last in operation, and what product it was running to make sure there are no compatibility or contamination issues.

Machines can vary in their suitability. “It can be ‘just right’—you can bring it into the room, plug it in and it will run your product with no problem. It can be ‘just right’ but needs new changeparts. It can be ‘almost right’ but needs some modifications or refurbishing,” Henry says. If it needs to be modified—perhaps to update or standardize on the controls—get that work going right away.

Arrange for the machine(s) to be moved to the new location. This may be as easy as rolling it from storage or wherever it is to the line. Or it could require careful crating, shipping and, possibly, reassembly. “Use qualified riggers,” Henry advises, to prevent damaging the system.

NEXT: Installation and commissioning

4. Install and commission the line

Will you be doing your own installation and commissioning? Even if you have the talent in-house, do you have the time? If you opt to use an outside contractor, qualify and select them as early as possible so they are included in the various stages of the process.

You might even be able to tap into another expert for the startup. “[The original] machine builders can be a useful resource,” Henry reminds us.

Remember training! “I’ve seen companies spend a billion dollars on a new line and then training consists of a couple hours of ‘Push this green button and the machine should run,’” Henry explains. “You need to train your people. They are running a million-dollar machine, and you want them to know what they are doing.”

Train workers on the line’s operation, changeover, setup and cleaning. Train your maintenance technicians on preventive and repair tasks.

NEXT: Turn it on, turn it up

5. Begin production

Henry recommends you plan on starting to run slowly at first and build up to production rate. “You’re going to do this anyway, whether you want to or not,” Henry says. “I’ve been involved in probably a thousand startups and, no matter how carefully we planned it—I always go into it optimistically…‘This time, I’m going to press a button and it’s going to run perfectly’—it’s always like Lucy with the football. It never, ever does.”

You might think you’re done now, but there’s one more important task. “Monitor your productivity and your efficiency,” Henry concludes. A 2% drop in efficiency equals 40 hours of lost productivity.

“Most people think 2% is not enough to worry about. It really, really is.”

Henry suggests installing monitoring features that allow you to do that in real time. “It doesn’t matter what the efficiency was last week. It’s too late to do anything about it. You need to know what your efficiency is right now at this moment. If it’s low, you can do something about it.”

He’s got an easy metric to remember: 10W40. Ten minutes of wasted time or downtime is 40 hours a year—or a full week—of lost production.

So when you’re putting together a Franken-line—or any packaging line, for that matter—look for efficiency. “Look for minimizing downtime,” says the changeover wizard. “It may cost you extra money. Spend it!”

Because it’s the cheaper alternative in the long run.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like