With a recycling rate of 38% in 2016 for expanded polystyrene (EPS), why are companies eliminating the affordable, reliable protective packaging material from their options?

The type of plastic you use for your packaging matters more and more, for various reasons—including consumer preference and environmental stewardship. Over the decades, companies have shied away from certain plastic packaging seen as unpopular or even harmful. Recently, as part of their sustainable materials management programs, Target and McDonald’s say they will be replacing expanded polystyrene (EPS) packaging with something else.

Eliminating EPS from Target-owned product packaging by 2022 is one of five new sustainable packaging goals for the retailer. Kim Carswell, a packaging director at Target, explains why:

1. “We noticed the guest frustration when they tried to recycle it, because it’s not easily recyclable.”

2. “It’s also a big issue in our distribution centers because a lot of product that gets sent to stores is taken out of the box and hung, like a mirror or a frame. But then the polystyrene has got to go back to the distribution centers and there’s a lot more than you would imagine. It’s just enough to be a problem but not enough to invest in densifiers.”

3. “And we know from an ocean plastics sense, EPS is one of the prime contributors. Per the New Plastics Economy work, there will be more pieces of plastic in the ocean than actual fish by 2050.”

But Carswell also says, “We know this material has got a lot of value. Today, polystyrene has a great cost, it’s very available and does a great job protecting the product. We want to be super careful in moving away from it.”

PlasticsToday reports that McDonald’s will phase out “harmful [EPS] foam packaging globally” after 31% of shareholders voted at its annual meeting on May 24, 2017, in favor of the action [see update below]. According to press reports, the nearly one-third vote “far exceeds the average voting result of 20% for social and environmental issue proposals.”

The vote was in response to urging from As You Sow, the environmental and social corporate responsibility advocacy group. In February 2017, it publicly asked four leading U.S. companies—Amazon, McDonald’s, Target and Walmart—to make plans to phase out polystyrene foam packaging. As You Sow cited the January 2017 report The New Plastics Economy—Catalyzing Action from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, which recommends replacement of polystyrene (PS), expanded polystyrene (EPS), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) as packaging materials.

Yet in July 2017, the Chicago Tribune reported that McDonald’s was bringing back foam cups in the area without giving a clear reason why. Conrad MacKerron, svp of As You Sow, was quoted in the article, saying, “It seems strange to bring something like this back. It’s kind of curious that they’re doing this now.”

[UPDATE 8-18-17: On Wed., Aug. 16, Conrad MacKerron from As You Sow sent an email saying that McDonald's had not agreed to phase out EPS. Upon further checking with McDonald's, asking specifically if the company had or had not agreed to this, a public relations representative declined to answer the question but instead sent this statement: "We continue to work with our suppliers on sustainable packaging options that reduce our sourcing footprint and positively impact the communities we serve."]

EPS recycling stats and industry response

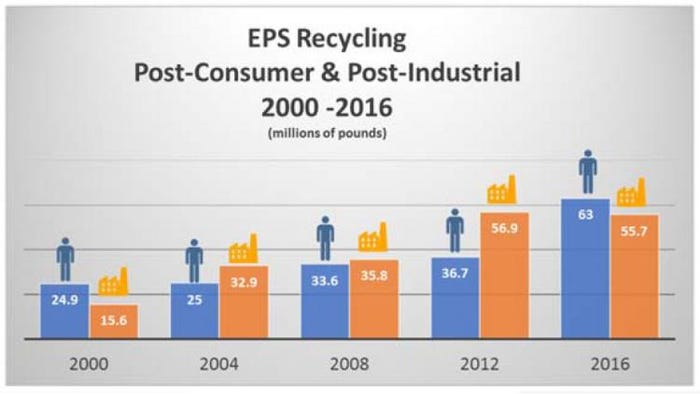

According to the EPS Industry Alliance, which represents expanded polystyrene manufacturers, EPS recycling has averaged about 18% over a 25-year period. Betsy Bowers, executive director of EPS-IA, says, “Despite minor fluctuation in quantities collected from year to year for post‐consumer versus post-industrial, overall EPS recycling has, and continues, to demonstrate consistent, long term growth.”

In 2016, the EPS recycling rate spiked to 38% and packaging is the majority of the material being recycled. A total of 118.7 million pounds of material were recycled, with 63 million pounds coming from post-consumer and post-commercial streams, and the rest, 55.7 million pounds, from post-industrial operations.

Source: EPS Industry Alliance

Despite the high recycling percentage cited by the industry group, companies are still shying away from EPS, decisions that EPS-IA says might not be based solely on science.

“Polystyrene bans are perceived as an environmental quick‐fix that, in reality, don’t deliver any benefits to minimize waste, increase recycling or diminish environmental impacts,” Bowers explains. “In California, 65 communities have banned polystyrene, while 57 have implemented polystyrene curbside recycling. While Target and McDonalds have succumbed to shareholder activism advocating polystyrene phase outs, WalMart, Williams Sonoma, NutriSystems and others have embraced widespread EPS recycling initiatives. Subaru implemented an international EPS reuse program, achieving ≥20 (re)uses per unit while saving $1 million in packaging costs. Which of these are environmentally progressive?”

She continues, “This begs the question, will recycling meet all our environmental goals? If recyclability is the sole benchmark of environmental worthiness, then all products that can’t be recycled would be banned. EPS‐IA challenges As You Sow, Target and others that may be entertaining EPS bans to seek better environmental solutions. Check the facts and rely on credible sources. Don’t cherry pick information to suit a pre‐determined outcome. Find out about alternative materials real‐world availability, and conduct due diligence on performance and environmental tradeoffs.”

(See page 2 for the text of Bowers full statement.)

Other plastic packaging phase outs

In an online poll conducted in Spring 2017, Packaging Digest and its sister publications PlasticsToday and Pharmaceutical & Medical Packaging News asked our global packaging communities if they were, indeed, phasing out certain plastics and, if so, was The New Plastics Economy initiative playing a role in their decision.

Download the free 8-page exclusive report below to see the results, shown by all respondents, by market (food; beverage; medical devices/supplies; electronics; household products; Rx or OTC pharmaceutical; personal care/cosmetics; media; and other) and by plastic type (expanded polystyrene/EPS; polyvinyl chlorine/PVC; polystyrene/PS; or other).

Full statement from Betsy Bowers, executive director, EPS Industry Alliance

Expanded Polystyrene (EPS) Foam Recycling Statistics 2016

Post‐Consumer & Post‐Commercial: 63.0 million pounds

Post‐Industrial: 55.7 million pounds

Total Recycled: 118.7 million pounds

These data points represent a finite number of survey respondents and may not include all EPS recycling. There were 45 survey respondents consisting of companies that reprocess EPS waste. To determine a recycling ‘rate’ or percentage, EPS‐IA relies on data for custom molded EPS production; 165.5 million pounds was reported in 2016. This determines a recycling rate of 38% for 2016. By comparison, in 2013 EPS‐IA published a 34% recycling rate even though there was significantly more material collected (almost 10 million pounds higher).

Historically, EPS recycling averages ~18% over a 25 year trendline. There have been two significant growth spurts, one in 2005 and most recently in 2013. Despite minor fluctuation in quantities collected from year to year for post‐consumer versus post‐ industrial, overall EPS recycling has, and continues, to demonstrate consistent, long term growth.

Post‐consumer includes curbside recycling, community drop‐off and other collection methods that are accessible by the general public. Post‐commercial includes EPS packaging or insulation that was recycled after it was used for its intended purpose by business entities within their internal operations. Examples include WalMart, Williams Sonoma, Whirlpool and Harley Davidson that may generate EPS waste from manufacturing automation lines or from within the product supply chain. While the majority of EPS being recycled is packaging, companies like Nationwide Foam Recycling are dedicated to recycling foam building insulation – including EPS – for reroofing projects throughout the U.S.

Shareholder Activism Against Polystyrene Foam

As You Sow’s polystyrene deselection campaign is an outdated and ineffective approach to solid waste management. Most frontline waste management solutions in this decade are dedicated to the hard work required to take recycling to the next level – not eliminating materials to make headlines, which is essentially what motivated the City of San Francisco when they made national news for banning polystyrene, for the second time, a quite interesting oxymoron.

Material bans – whether for polystyrene foam, plastic bags, bubble wrap, paper coffee cups or any other material that is more difficult to recycle – are not an effective solid waste solution for a variety of reasons. Product bans are not a proven solid waste management strategy. Political motivations often override scientific facts. Substitute materials are not adequately vetted, from a performance or environmental perspective.

Product Bans Are Not A Proven Solid Waste Solution

Gary Toebben, President & Chief Executive of the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce, comments on “Why Polystyrene Bans Do More Harm Than Good”, in the Los Angeles Times on January 6, 2017.

The City of Austin conducted a formal research study, Environmental Effects of the Single Use Bag Ordinance, published in June 2015 concluding that while some of the original goals were achieved, there were notable unintended consequences.

Patrick Gleason, when contributing his opinion to Forbes in “State And Local Bag Taxes And Bans Face Pushback”, claims bag bans and taxes have been a failed policy experiment.

Recently Chicago repealed its plastic bag ban, preceded by Erik Telford’s article, “Chicago’s Misguided Plastic Bag Ban”, in the Chicago Tribune early last year.

On July 1, 2017 San Diego citizens will have access to polystyrene foam recycling in their blue bin collection as reported by the San Diego Union‐Tribune on June 20, 2017, “Instead of Ban, San Diego Will Allow Recycling of Foam Food Containers”. This decision followed a detailed review by the City Council including relevant impact studies by local agencies.

Science Matters When It Comes to Sound Environmental Decision Making

In the preamble to its second polystyrene ban proposal, the City of San Francisco cited the U.S. EPA as reporting polystyrene as a serious human health threat, however they refused to substantiate the reference with a citation and conversely, EPA’s website states, “the evidence is inconclusive due to confounding factors” in reference to styrene monomer, an organic chemical compound used to produce EPS. They further referenced “Quantity & Type of Plastic Debris Flowing From Two Urban Rivers to Coastal Waters & Beaches of Southern California”, stating 71% of microplastics found in the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers were polystyrene foam pieces. The study was about litter and cited all foam as 71% of which 11% by weight was expanded (foamed) polystyrene. San Francisco is just one example for EPS ban proponents to distort or misrepresent environmental facts.

Environmentally relevant concentrations of microplastic particles influence larval fish ecology,” initially named polystyrene as an indiscriminate culprit when released in June 2016. This May, the Central Ethical Review Board announced its recommendation the research results be retracted due to missing data and problematic methodology.

San Francisco Estuary Institute refused to divulge supporting information to its claim that ‘foamed plastic particles’ constitutes 8% surface water samples in Rebecca Sutton’s study, Microplastic Contamination in San Francisco Bay. After this figure was used to support the City of San Francisco’s second polystyrene ban proposal, it was picked up on several local news stations and published in numerous print media outlets. SFEI’s definition of foamed plastic includes cigarette filters, a significant detail considering cigarettes are the largest source of litter worldwide.

Substitute Materials

When banning polystyrene, Ecovative’s mycelium product is often mentioned as a viable alternative. Dell Computer, Sealed Air and other trusted household names are associated with this fledgling company which still identifies itself in the transfer technology stage. Their website also asserts “Ecovative has not yet published a peer reviewed Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)” but continues to claim its environmental superiority over traditional foam plastics without substantiation. Merck Forest & Farmland is using Ecovative for 1,000 units/year. And, while Dell has ultimately been successful in relaunching Ecovative ‘for select shipments’, this came after a pilot prototype launch in 2013 that according to Dell, “needed additional testing before introducing it as a widespread alternative to existing expanded polyethylene cushioning….hurdles in terms of continuity and supply and material cost”. Material innovation is laudable but should not be overstated prematurely in the misguided efforts to ban EPS.

Formal EPS‐IA Statement

Polystyrene bans are perceived as an environmental quick‐fix that in reality don’t deliver any benefits to minimize waste, increase recycling or diminish environmental impacts. In California 65 communities have banned polystyrene, while 57 have implemented polystyrene curbside recycling. While Target and McDonalds have succumbed to shareholder activism advocating polystyrene phase outs, WalMart, Williams Sonoma, NutriSystems and others have embraced widespread EPS recycling initiatives. Subaru implemented an international EPS reuse program, achieving ≥20 (re)uses per unit while saving $1 million in packaging costs. Which of these are environmentally progressive?

This begs the question, will recycling meet all our environmental goals? If recyclability is the sole benchmark of environmental worthiness, then all products that can’t be recycled would be banned. EPS‐IA challenges As You Sow, Target and others that may be entertaining EPS bans to seek better environmental solutions. Check the facts and rely on credible sources. Don’t cherry pick information to suit a pre‐determined outcome. Find out about alternative materials real‐world availability, and conduct due diligence on performance and environmental tradeoffs.

“Let’s stop fooling ourselves about the efficacy of bans and actually roll up our sleeves and do the hard work” is great advice from Gary Toebben, President & Chief Executive for the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. EPS‐IA encourages corporate America as well as local communities to embrace environmental decision making with context.

Note: Of interest, the Ellen McArthur Foundation New Plastics Economy reports reference indirect and/or nebulous sources in reference to polystyrene foam and neglect to make any references – at all – to the environmental benefits of EPS. It therefore appears to be bias against polystyrene.

****************************************************************************************

Learn what it takes to innovate in the packaging space at MinnPack 2017 (Nov. 8-9; Minneapolis). Register today!

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like