Packages: Tracing an evolution

February 1, 2014

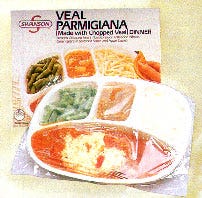

TV dinners go plastic

Like so many packagers do, C.A. Swanson & Sons took cues from the airlines in the 1950s when it had too much leftover turkey. As the story goes, Swanson TV dinners got their start in 1953 when Gerald Thomas, a Swanson executive, had to decide what to do with a whopping 270 tons of leftover, unsold Thanksgiving turkey. So, the first Swanson TV dinner, roast turkey with stuffing and gravy, mashed potatoes and peas, sold for a reported 98 cents and came in an aluminum tray, with a printed outer paperboard carton. The aluminum tray concept supposedly came from trays used by the airlines. Anyway, the trays and the TV dinners were a hit, and still are, though PD hears Swanson stopped calling them TV dinners in 1962 and soon added desserts to the compartmented trays.

Decades later in 1986, when Swanson was a unit of Campbell Soup Co., the aluminum tray was placed in the Smithsonian Institute, next to Fonzie's jacket, and took an eternal commercial break, as Campbell converted all 18 of the Swanson frozen dinner  varieties to a four-compartment tray of crystallized polyethylene terephthalate that was covered in clear polyester film (see PD, June, '86, p. 34 and p. 96). PD reported that the cost of the conversion was nearly double, but the justification at the time was microwavability. Reports Swanson on its "In the News" website, "The advent of the microwave oven and other appliances has made dinner preparation faster and easier. Now that moms have gone to work, frozen meals are becoming more popular." Campbell's production of the Swanson line at the time was noteworthy, PD reported, "for its self-manufacturing." The article continues, "While some of the Swanson trays are supplied by outside vendors ... most are made in-house." At that time, Campbell made millions of the CPET trays on a sophisticated captive-tray extrusion/thermoforming line at its Modesto, CA, plant. The change signaled a move to plastics by many packagers for various frozen and nonfrozen food products. This year, Swanson is celebrating 50 years of TV dinners.

varieties to a four-compartment tray of crystallized polyethylene terephthalate that was covered in clear polyester film (see PD, June, '86, p. 34 and p. 96). PD reported that the cost of the conversion was nearly double, but the justification at the time was microwavability. Reports Swanson on its "In the News" website, "The advent of the microwave oven and other appliances has made dinner preparation faster and easier. Now that moms have gone to work, frozen meals are becoming more popular." Campbell's production of the Swanson line at the time was noteworthy, PD reported, "for its self-manufacturing." The article continues, "While some of the Swanson trays are supplied by outside vendors ... most are made in-house." At that time, Campbell made millions of the CPET trays on a sophisticated captive-tray extrusion/thermoforming line at its Modesto, CA, plant. The change signaled a move to plastics by many packagers for various frozen and nonfrozen food products. This year, Swanson is celebrating 50 years of TV dinners.

Standing ovation for pouches

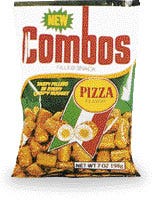

The flexible packaging market includes all kinds of pouches, but the popular standup variety has especially changed the standard of living in the U.S., according to a quote from Roger Conant, formerly with Jefferson Smurfit Corp., in a Flexible Packaging Assn. publication entitled "The FPA Story, 1950-2000." Consumers don't have to look far to find examples of how  flexible packaging has changed consumer lifestyles. Head to the local supermarket, which features flexible packs for everything from snack crackers to diapers. And with the breakthrough of reclosable zipper features that heighten convenience, standup reclosable pouches have dramatically expanded into new markets and have helped create new products. Almost everything is being looked at as ideal in a standup pouch these days, including products that previously required rigid containers, such as soups. Prewashed and cut, ready-to-eat carrots and salads, packed under modified atmosphere, might have never become a convenience reality had it not been for flexible pouches.

flexible packaging has changed consumer lifestyles. Head to the local supermarket, which features flexible packs for everything from snack crackers to diapers. And with the breakthrough of reclosable zipper features that heighten convenience, standup reclosable pouches have dramatically expanded into new markets and have helped create new products. Almost everything is being looked at as ideal in a standup pouch these days, including products that previously required rigid containers, such as soups. Prewashed and cut, ready-to-eat carrots and salads, packed under modified atmosphere, might have never become a convenience reality had it not been for flexible pouches.

Decades ago, only one clear film could be used as a packaging material, and that was cellophane. In the 1960s, when space travel, civil rights and the environment came into view, flex-packs started to evolve, with processes and materials in a state of constant change. Individually quick-frozen vegetables were unveiled in flexible bags. Laminated foil/paper bags for snacks and cookies emerged. While many bags and pouches were made of coated papers, polypropylene and polyethylene came along, followed by coextrusions, coatings and laminations.

According to FPA, plastic consumption by flexible packagers grew at double-digit rates throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Preformed pouches got jump-started in the early 1960s, along with heat-sealing developments. Laminations and coextrusions were hailed as two of the biggest breakthroughs in packaging. And in 1963, the new AMF Mark 50 bread bagger revolutionized the way bread was processed, moving the conventional use of roll-fed overwraps to PE bags for bread and other bakery products, having an incredible impact on the packaging community. In the decades that followed, with new packaging regulations, ecology, corporate mergers and raw material shortages, more pouches were being made of film instead of paper and foil; metallized PP began to replace cellophane and glassine as packaging materials for snack foods, and later coex films made in a single pass led the way for meat packs, hot dogs and other products.

Capri Sun juice drinks in standup pouches were at the forefront of a standup pouch uprising in the 1980s along with vacuumized coffee pouches in sleek, glitzy gabled pouches. But it wasn't until the late 1980s/early 1990s that standup pouches as we know them today truly established themselves as a strong market presence and made a major market impact by replacing other types of containers. Nabisco Biscuit's snack pack introduction for Ritz and Snack-Wells in the mid-'90s broke ground with its gusseted standup pouches made on new horizontal Doyn-style form/fill/seal systems (see PD, Jan., '96, p. 48). Standup pouches used as refills were also being designed as companions for rigid bottles of products, from glass cleaner to hand lotion, as a source reduction or a way to "precycle." Petfoods led the way with large, heavy-duty standup film pouch structures, some with handles, reclosable features and more, as replacements for multiwall bags. Low-density PE, metallized oriented PP and other new materials were extending shelf life, preserving flavor and deterring moisture.

The list of developments could go on and on throughout the 1990s, as many equipment makers, material suppliers and packagers continued in their quests to establish the flexible pouch and the standup pouch as formidable alternatives to rigid packaging through refinements, improvements and vertical integration. And that's just for starters–we have only just entered the new millennium.

The list of developments could go on and on throughout the 1990s, as many equipment makers, material suppliers and packagers continued in their quests to establish the flexible pouch and the standup pouch as formidable alternatives to rigid packaging through refinements, improvements and vertical integration. And that's just for starters–we have only just entered the new millennium.

Retort pouches kick the can

In widespread commercial use today, the retort pouch gained popularity in part from developments in frozen foods and with the armed forces. In fact, food rations, in MRE (meals, ready to eat) packages for the military, officially known as trilaminate retort pouches, were essentially where retort pouches–created as "flexible cans"–probably got their start. Made out of thick foil and film  layers, those retort pouches have been refined since first developed for the military and have since lived many lives, for products from moist petfood to baby food. In 1987, PD reported that the retort pouch was seeing a revival, as Gainers of Canada, whose Kretchmar line of entrées was being packaged in what was described as "all-plastic" (polyester/saran/PP) pouches. The pouches reportedly sold so well in St. Louis, that distribution expanded to New York and New England. Pouch supplier Ludlow Flexible Packaging reported on the coming-from-behind success at a Future-Pak conference back in 1986. Such nonfoil pouches appealed to microwave-oven users of the time, and the federal government was said to be buying up more retort-pouch-packed military rations than ever in 1987. Retort pouches were also gaining ground toward the end of the 1980s and early 1990s, for three big advantages over cylindrical metal cans: They were lighter, which made them attractive as a source reduction, they were flexible, meaning that they could handle abuse in the field, and they were flat and portable, adding to the convenience factor of carrying them.

layers, those retort pouches have been refined since first developed for the military and have since lived many lives, for products from moist petfood to baby food. In 1987, PD reported that the retort pouch was seeing a revival, as Gainers of Canada, whose Kretchmar line of entrées was being packaged in what was described as "all-plastic" (polyester/saran/PP) pouches. The pouches reportedly sold so well in St. Louis, that distribution expanded to New York and New England. Pouch supplier Ludlow Flexible Packaging reported on the coming-from-behind success at a Future-Pak conference back in 1986. Such nonfoil pouches appealed to microwave-oven users of the time, and the federal government was said to be buying up more retort-pouch-packed military rations than ever in 1987. Retort pouches were also gaining ground toward the end of the 1980s and early 1990s, for three big advantages over cylindrical metal cans: They were lighter, which made them attractive as a source reduction, they were flexible, meaning that they could handle abuse in the field, and they were flat and portable, adding to the convenience factor of carrying them.

Kraft's a la Carte, ITT Continental's Continental Kitchens brand, had limited supermarket distribution of retort-pouched entrées in the late '80s, but supermarket shoppers weren't yet convinced about buying pouched entrées from dry grocery shelves. The Kretchmar line avoided that by being sold in the meat department's refrigerated case, though refrigeration wasn't really required for the products. While there were others, it wasn't really until 2000 that StarKist tuna made a huge splash in the market with retort pouch technology. Its convenient, time-saving retort foil pouch (see PD, July, '00) containing 7.06 oz was vacuum-sealed foil and required no messy draining. The package posted an 18-month shelf life. Michael Mullen, a StarKist executive, pointed out that the "most important advantage o f the packagae was that the product in the pouch was of a higher quality and better tasting [than tuna in the can]," because of how the product was processed. "With the flat pouch, we only have to retort it for forty-five minutes, versus four hours in a can, to kill off bacteria," he added. That made huge breakthroughs in both the cost of production and the quality of the food, PD is told. With more research, retort pouches will continue to make breakthroughs as vehicles to introduce more products.

Portable is the way to-go

Ever since the nomads used animal skins to carry food, packaging has protected food for travelers and others on-the-go. In the 1960s, one key portable food container was the Thermosw, which has actually helped provide the hottest, coolest and freshest products. While packagers were onto something with the convenience of frozen TV dinners in the 1950s, packaging advancements and product developments continued the convenience and totable theme for people who were driving more, working more outside the home and dining more away from home.

Breakfast got a boost in the 1960s with mini cereal bag-in-boxes printed to look exactly like the full-sized cereal boxes, but with cereal that could actually be eaten right out of the package, with milk added (the single-serve cereal packs  are still hugely successful with kids today). Carry-out cartons, doggie bags, metal lunch boxes and small meal kits were popular or gaining popularity, and later, paperboard cartons for frozen entrées were a norm. In the 1970s, convenience foods and fast foods were emerging. Space Food Sticks developed for the Space Program in the 1970s, weren't exactly a meal, but became a portable paper/foil-laminate-wrapped snack hit and went well with Tangw. As more microwave ovens went into households in the 1980s, modified atmosphere and shelf-stable foods also seemed to be sprouting up everywhere. Foods packed to go came in thermoformed and molded plastic trays, bowls and clamshells. Lunchtime seemed to be a key target time for portable feasts, and kids in the 1980s were wowed by Oscar Mayer's launch of Lunchables portable meal kits.

are still hugely successful with kids today). Carry-out cartons, doggie bags, metal lunch boxes and small meal kits were popular or gaining popularity, and later, paperboard cartons for frozen entrées were a norm. In the 1970s, convenience foods and fast foods were emerging. Space Food Sticks developed for the Space Program in the 1970s, weren't exactly a meal, but became a portable paper/foil-laminate-wrapped snack hit and went well with Tangw. As more microwave ovens went into households in the 1980s, modified atmosphere and shelf-stable foods also seemed to be sprouting up everywhere. Foods packed to go came in thermoformed and molded plastic trays, bowls and clamshells. Lunchtime seemed to be a key target time for portable feasts, and kids in the 1980s were wowed by Oscar Mayer's launch of Lunchables portable meal kits.

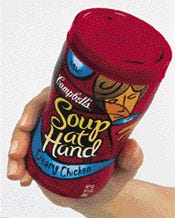

Soon, there were Lunch Buckets, Soup for One containers and fresh-refrigerated soups and salads in glass jars. In 1989, Hormel's Top Shelf beef, chicken, fish and pasta, shelf-stable dinners could go from the microwave to the table in their own plastic dishes, and General Foods launched its Ipromptu line.

And, while McDonald's was a hit in fast food, packagers were expanding on carry-out ideas and developing convenience foods of their own, such as sandwiches in modified atmosphere film packs, like Owens Country Sausage in barrier-film blisters (see PD, April, '86, p. 55) and Simplot's Microwavable French Fries in single-serve cartons. One of the latest in packaging portability is Campbell's Soup at Hand line, which followed its Soup to Go soup in a foam-covered plastic retort cup. Introduced during the Food Marketing Institute show in May, 2002, the mega-portable Soup at Hand's single-serve container fits in a car's cupholder and contains 10.75 oz of microwavable soup in a tall, foam-labeled plastic can with a metal rim and metal pull ring, much like that of Soup To Go. There are Smithfield Packing's heat-and-eat microwavable, precooked entrées, Kellogg's prefilled cereal bowls with peelable lidding for Breakfast Mates cereal/milk combinations and Yoplait's successful Go-Gurt™ yogurt in a film tube. Have the yogurt with a side of Del Monte Foods' Fruit To-Go in a clear, gas-flushed plastic single-serve cup with a peel-off lid, and breakfast is served. There are stick-packs for pudding, fresh lettuce salads in clear plastic shakers, retort pouches for cooked rice and home-meal-replacements such as Pasta Anytime meal kits. On the go or not, consumers still have to eat.

Microwavable meal in a bowl

Just when microwave ovens were becoming commonplace in offices, convenience stores and at home, the Lunch Bucket line of microwavable meals in barrier containers was launched by the Dial Corp. Though details were sketchy, the 8-oz bowl-like container, a 1987 DuPont Award winner, was said to be the first use of a commercial high-barrier coextruded cup made by the closed-loop, rotary thermoforming (RTF) process.  The cup was described as having seven plastic layers and was sealed with a full-panel, easy-open aluminum end topped with a plastic overcap that was vented for use in microwave ovens. A printed foam wraparound label served as an "oven mitt" when Lunch Bucket was heated (see PD, Feb., '88, p. 44 and Jan. '87, p. 92). Dial's container was thought to include an ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer core layer with outer layers of PP. In the symmetrical structure, both the layers and the regrind were believed to be used. The package has continued to evolve, as several generations of development went into the all-plastic package as it is today, and it has since won additional DuPont Awards.

The cup was described as having seven plastic layers and was sealed with a full-panel, easy-open aluminum end topped with a plastic overcap that was vented for use in microwave ovens. A printed foam wraparound label served as an "oven mitt" when Lunch Bucket was heated (see PD, Feb., '88, p. 44 and Jan. '87, p. 92). Dial's container was thought to include an ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer core layer with outer layers of PP. In the symmetrical structure, both the layers and the regrind were believed to be used. The package has continued to evolve, as several generations of development went into the all-plastic package as it is today, and it has since won additional DuPont Awards.

Dual-ovenable micro 'wave' of the future

Not until the mid-1980s, when about half of U.S. consumers owned microwave ovens, did the food industry see significant market potential for microwavable foods. That's when the phrase "dual-ovenability" for microwavable/ ovenable packaging started to stick. In 1986, PD predicted that by the turn of the 21st century, most U.S. consumers would be equipped with microwave ovens. In the 1980s, more foods and packaging were being developed especially for use in the microwave oven only, including popcorn, pizza, sandwiches and entrées, but there was also more demand for dual-ovenable packaging. Since foil packaging was problematic in a microwave oven, causing arcing, microwave fires and magnetron destruction, paperboard containers seemed a logical route.

But dual-ovenables faced the challenges of having to be dimensionally and temperature-stable, both before and after heating, sanitary and durable, immune from contributing off-flavors to foods, visually attractive, microbiologically safe and capable of withstanding the demands of food processing, oven heating temperatures–both in the conventional oven and in the microwave oven–and withstand  the rigors of storage, shipping and handling. Adoption of such containers often required at least partial replacement of existing packaging machinery, not to mention new container converting techniques.

the rigors of storage, shipping and handling. Adoption of such containers often required at least partial replacement of existing packaging machinery, not to mention new container converting techniques.

One breakthrough came in the early 1980s with the all-folded paperboard container and lid for Budget Gourmet® from Westvaco's Ovenware group that still thrives today. Colorfully printed, this economical package withstood the economic recession that forced many high-packaging-cost products off supermarket shelves.

Molded paper trays also came on the scene for microwavable products as did multilayer barrier containers for microwavable, shelf-stable entrées. Heat susceptors bonded to paperboard, patterned susceptors and doneness indicators also came into the picture.

In 1986 came what was called the Cook-In-Box, an SBS paperboard container developed by International Paper and used by Patterson Foods, Patterson, CA, for frozen vegetables. The carton was coated both-sides with PE, which provided a good heat-seal during cartoning and prevented moisture from leaking out into the oven, according to aPD article in July, 1986, entitled "Microwavables impact packaging." Frozen foods were among the first to be packed in dual-ovenable containers, including coated paperboard cartons for microwavable potatoes from Marsh Supermarkets and Stouffer's Lean Cuisine, which went into national distribution. And, while some packagers preferred emphasizing "microwave-only" packaging, visionaries saw that dual-ovenability was the true micro "wave" of the future. As George Caster, grocery merchandiser in the mid-'80s for Marsh Supermarkets, based in Yorktown, IN, at the time, predicted, "The packaging industry still has an ace in the hole with dual-microwavable/ovenable packages that can be used in both conventional and microwave ovens. I think it's a must for frozen food products to go in that direction. We're already seeing more and more products that have this dual feature. I consider it the package of the future for frozen foods."

Modified atmosphere packaging

Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP), which is the process of changing the gaseous environment in a package to extend the shelf life of its contents, is used for a wide range of products, including fresh fish and meat,  poultry, sausages, entrées, bakery products, pasta, pizza, fruit, vegetables and many other food items. Vacuumizing technology, the first type of MAP to be used, was introduced in the 1960s in the U.S. to package chicken and was also used for raw meat and luncheon meat packaging. Gas-flush f/f/s got its start later that decade for coffee, and the technology was extended to a wide array of package forms, including flexible packages, cups and trays. The 1980s and '1990s saw a considerable expansion in the number of modified-atmosphere packaging machines, and it was during this period that it began to be applied to flexible packages of fresh products, such as lettuce. Oxygen scavengers were commercialized and permeable packaging films were also developed during this period.

poultry, sausages, entrées, bakery products, pasta, pizza, fruit, vegetables and many other food items. Vacuumizing technology, the first type of MAP to be used, was introduced in the 1960s in the U.S. to package chicken and was also used for raw meat and luncheon meat packaging. Gas-flush f/f/s got its start later that decade for coffee, and the technology was extended to a wide array of package forms, including flexible packages, cups and trays. The 1980s and '1990s saw a considerable expansion in the number of modified-atmosphere packaging machines, and it was during this period that it began to be applied to flexible packages of fresh products, such as lettuce. Oxygen scavengers were commercialized and permeable packaging films were also developed during this period.

Meat becomes case-ready

Prior to the 1960s, in the retail meat market, carcasses were shipped to retailers for breaking and cutting. In the late 1960s, the process of extrusion laminating was developed, and barrier bags with high-abuse properties made "boxed beef" programs possible, whereby smaller pieces called primals and subprimals were placed in vacuum-packaged bags by the meat packer. This allowed supermarkets to manage their meat case inventories and offer a greater variety of meat cuts while curbing waste. Boxed meats also made shipping and distribution easier because meat could  be stacked in boxes, and warehouse and supermarket employees were better able to handle the boxed product. The late 1960s also saw the advent of modified atmosphere packaging, which was later used as an alternative for packaging case-ready meats. In 1971, an article in PD stated that "about three percent of the companies operating supermarkets do some central prepackaging of fresh retail cuts."

be stacked in boxes, and warehouse and supermarket employees were better able to handle the boxed product. The late 1960s also saw the advent of modified atmosphere packaging, which was later used as an alternative for packaging case-ready meats. In 1971, an article in PD stated that "about three percent of the companies operating supermarkets do some central prepackaging of fresh retail cuts."

In 1972, PD reported that a Forest Park, IL, meat packer, E.W. Kneip, Inc., had begun using a CO2 gas MAP system for packaging bulk boxes of beef. According to the article, "The result is extended shelf life and improved appearance, without the use of a shrink tunnel or CO2 pellets or snow, plus space and labor savings."

By the 1980s, individual retail cuts were being vacuum-packaged or MAP-packed at a central location. In 1999, Cryovac introduced an innovative new oxygen scavenger film, OS1000, said to be the world's first polymer-based oxygen scavenging system, which eliminated residual oxygen from packages packed under low-oxygen, modified-atmosphere conditions. The new technology, for use with processed or dried meat products, not only gave processors an alternative to putting oxygen-scavenging packets into their products, but it also provided an entirely new way of using films to rid packages of residual oxygen, which can lead to discoloration, off-flavors and even mold in meats.

The OS1000 packaging system, consisting of a barrier foam tray fitted with a unique peelable barrier film lid, gave processors up to 18 days to move packages of case-ready fresh ground beef to the retailer in a low-oxygen environment. At the supermarket, retailers then peeled off the barrier portion of the film serving as an oxygen barrier, allowing oxygen to enter and the meat to regain its full red color in what is called a "blooming" process. With the barrier layer removed, leaving a thinner permeable film layer, the beef could retain its color for 48 hours–about double the time a typical store-pack of beef could retain color at that time.

By 2001, PD reported, "In case-ready meat packaging, there is plenty of growth in flexible film usage with clear, anti-fogging materials, barrier films, high-abuse shrink films and other major materials used for packaging."

The article continued: "The American Meat Institute (AMI) also finds a noticeable trend toward production of more case-ready red meat products that are prepackaged, with retail stores moving some 1.2 billion packages in 2000, which is more than double the number sold in 1997. AMI says industry experts see the potential to sell 9 million packages.

"Case-ready packaging is expected to expand rapidly over the next few years. Stores using such products on average have experienced a 3.8-percent growth in sales within their meat departments, according to a January, 2001, study conducted by Cryovac Div., Sealed Air Corp.

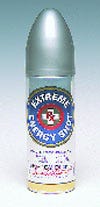

Aluminum beverage cans pour it on

Beverage cans made from aluminum were first introduced in 1965, and by 1985, they dominated the beverage market. Last year, more than 100 million aluminum beverage cans were shipped in North America. Currently, they have about half  of the single-serve market and 85 to 90 percent of the multipack market for soft drinks. For beer, the mix for both single-serve and multipacks is about 50/50 between glass and cans. Aluminum cans have also begun to move into the bottled water market, and have found a niche in energy drinks. A recent innovation is the shaped can, in which the can takes on a customized shape. Aluminum cans have many benefits that have led to their success, including a light weight, corrosion-resistance and the ability to maintain the fizz of the beverage. They also heat and chill quickly, are a good material on which to print and can be recycled (aluminum beverage cans contain more than 50 percent recycled content). Aiding their acceptance has been the move to lighter weights; over the past 10 years, the wall thickness of the can has been reduced so that its metal content has been cut in half.

of the single-serve market and 85 to 90 percent of the multipack market for soft drinks. For beer, the mix for both single-serve and multipacks is about 50/50 between glass and cans. Aluminum cans have also begun to move into the bottled water market, and have found a niche in energy drinks. A recent innovation is the shaped can, in which the can takes on a customized shape. Aluminum cans have many benefits that have led to their success, including a light weight, corrosion-resistance and the ability to maintain the fizz of the beverage. They also heat and chill quickly, are a good material on which to print and can be recycled (aluminum beverage cans contain more than 50 percent recycled content). Aiding their acceptance has been the move to lighter weights; over the past 10 years, the wall thickness of the can has been reduced so that its metal content has been cut in half.

Ring-pulls ease can openings

The sound is impossible to miss, the loud pop that it makes as a can of beer or pop is opened. The stay-on tab that we all know so well has been around since the late 1970s and is a fixture in the North American beverage industry. But its predecessor, the ring-pull tab, lived a good life–it stills does in some Far East countries–as it was the solution to the dilemma of how to open a beverage can without a can opener. The ring-pull was first seen in the latter half of 1962, when Alcoa supplied it to the Pittsburgh Brewing Co. for its Iron City brew (see Modern Packaging, Nov., '62, p. 105). The design consisted of an aluminum tab that was integrally riveted to the can's aluminum lid. Consumers would pull up and outward on the ring to remove the tab, revealing a keyhole-shaped opening large enough to permit simultaneous air intake and pouring. However, its drawbacks, including cut fingers and disposed tabs on beaches and on the ground in picnic areas, eventually led to the development of the stay-on. Reynolds Metals Co. began supplying the stay-on to Coca-Cola in 1976 (see PD, Jan., '76, p. 54). While the stay-on tab has been the mainstay in beverage packaging since, the ring-pull has found new avenues of use. It is often used today for applications such as canned fruit, bean sprouts and soups, as well as many on-the-go packages, where the ring-pull is used to remove the entire can top.

Cans and containers begin shaping up in stores

The mid- to late 1990s brought the manufacturing of cans, bottles and other various containers into new dimensions. As seen with the introduction of the Milk Chug by Dean Foods and later with Coca-Cola's Contour can, the beverage  industry was instrumental in the beginning of the shaped container trend. Interestingly, the shaped containers had mixed results. The Chug was a hit with shoppers and maintains a strong presence in the dairy case today; the Contour can never quite caught on and is no longer in production. However, the shaped can market has gained interest in the beer industry, particularly recently with Heineken's Keg Can. The use of shaped cans brought new processes and technology to the can market. Crown Holdings developed a proprietary blow-molding process for shaping cans and a variety of other capabilities, such as embossing, have been developed.

industry was instrumental in the beginning of the shaped container trend. Interestingly, the shaped containers had mixed results. The Chug was a hit with shoppers and maintains a strong presence in the dairy case today; the Contour can never quite caught on and is no longer in production. However, the shaped can market has gained interest in the beer industry, particularly recently with Heineken's Keg Can. The use of shaped cans brought new processes and technology to the can market. Crown Holdings developed a proprietary blow-molding process for shaping cans and a variety of other capabilities, such as embossing, have been developed.

Coca-Cola leads renaissance in soft drink bottling

Beating competitor Pepsi-Cola to the finish line by a nose, Coca-Cola began the national rollout of its 2-L PET bottle, starting in Spartanburg, NC, as of November, 1977, PD reported. Coke had initially made plans to debut in plastic with an acrylonitrile (AN) bottle, but it was forced to do an about-face when the Food & Drug Administration banned the substance for use in beverage packaging in October of  that year (FDA had suspended its approval of the substance for such applications in March).

that year (FDA had suspended its approval of the substance for such applications in March).

Tests conducted by the Manufacturing Chemists Assn. on rats fed AN-laced drinking water showed weight loss and pathological changes in the brain, ear, breast and stomach over a period of one year (see PD, March, '77, p. 1). Pepsi, which had opted for a PET launch from the get-go, chose to initially offer bottles in the regular–for the time–pint and quart sizes. These developments came at an interesting time in plastics packaging where everything, from material characteristics and components to measurement units, was under heated debate. One thing that didn't require significant debate was the success of the 2-L PET soft drink bottle. It quickly became a staple in supermarkets throughout the 1980s and remains a major component of the soft drink industry today.

Aseptic drink boxes approved

Aseptic drink boxes were approved for sale in the U.S. in 1981, and became the hottest new concept the U.S. food industry had seen in years. They had been in use in other parts of the world for nearly 20 years, but the key to their acceptance  in the U.S. was the approval by FDA of hydrogen peroxide and heat as sterilizing agents for the packaging materials. Tetra Pak and Combibloc PKL were the primary suppliers of drink box machines, while International Paper had a machine in development. The Tetra Pak and IP machines were vertical f/f/s designs that produced packages from a web of material, while the Combibloc machine ran premade sleeves on a horizontal unit. The primary reason for their immediate success was their long shelf life–up to nine months or more–without refrigeration, but they offered significant other benefits. The multilayer package cost much less than bottles or cans, and the easily handled rectangular shape maximized storage, shipping and shelf space.

in the U.S. was the approval by FDA of hydrogen peroxide and heat as sterilizing agents for the packaging materials. Tetra Pak and Combibloc PKL were the primary suppliers of drink box machines, while International Paper had a machine in development. The Tetra Pak and IP machines were vertical f/f/s designs that produced packages from a web of material, while the Combibloc machine ran premade sleeves on a horizontal unit. The primary reason for their immediate success was their long shelf life–up to nine months or more–without refrigeration, but they offered significant other benefits. The multilayer package cost much less than bottles or cans, and the easily handled rectangular shape maximized storage, shipping and shelf space.

Plastic beer bottles make the scene

A brief news item in the August, 1975, issue of PD mentioned that Coors might soon add a plastic beer bottle based on a nitrile resin, if tests were successful. However, this bottle apparently was never introduced and was never mentioned again.  The first plastic beer bottles in the U.S. were introduced by Miller Brewing in October, 1998, for 16- and 20-oz and 1-L packages of Miller Lite, Miller Genuine Draft and Icehouse. The 1-L package was soon discontinued. Miller was followed into the plastic bottle market by Anheuser-Busch in April, 1999, when it began test marketing its leading beer brands in 16-oz plastic bottles. However, this test lasted only a short time, after which A-B abandoned the project because of "limited consumer interest." The plastic bottles used by both Miller and A-B were co-injection stretch/blow-molded from a multilayer structure of PET and oxygen scavengers. Continental PET Technology supplied the Miller bottles, while the A-B bottles were supplied by Amcor.

The first plastic beer bottles in the U.S. were introduced by Miller Brewing in October, 1998, for 16- and 20-oz and 1-L packages of Miller Lite, Miller Genuine Draft and Icehouse. The 1-L package was soon discontinued. Miller was followed into the plastic bottle market by Anheuser-Busch in April, 1999, when it began test marketing its leading beer brands in 16-oz plastic bottles. However, this test lasted only a short time, after which A-B abandoned the project because of "limited consumer interest." The plastic bottles used by both Miller and A-B were co-injection stretch/blow-molded from a multilayer structure of PET and oxygen scavengers. Continental PET Technology supplied the Miller bottles, while the A-B bottles were supplied by Amcor.

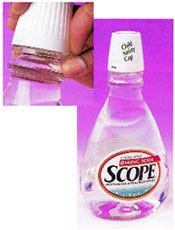

Child-resistant/senior-friendly packaging

Child-resistant (CR) packaging, a term synonymous with poison-prevention packaging (PPP), can be defined as a container that precludes entry by children under the age of five years but not adults to hazardous substances. Designs for CR packaging can be traced back to 1880, when the first U.S. patent was issued for a CR package. But it wasn't until 63 CR-packaging patents later, in 1966, that Congress began taking a  direct interest in this issue, due to public concern about the large number of children who were killed or seriously injured each year due to their ingestion of dangerous household substances. These harmful products included everything from solvents, chemicals and pesticides to prescription and OTC drugs.

direct interest in this issue, due to public concern about the large number of children who were killed or seriously injured each year due to their ingestion of dangerous household substances. These harmful products included everything from solvents, chemicals and pesticides to prescription and OTC drugs.

On December 30, 1970, President Nixon signed into law the U.S. Poison-Prevention Packaging Act (PPPA), which was initially placed under the jurisdiction of FDA and later (May, 1973) was regulated by the newly formed U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). The first test procedures, or protocol, for the evaluation of CR packaging were published in 1971. Under the protocol, children and adults are both given packages to open; only those packages that successfully deter small children, but can still be opened by adults, are considered acceptable.

The most typical forms of CR packaging include blister-packs and bottles with CR closures. Closure designs usually incorporate two dissimilar, simultaneous motions in order to activate or open a unit, such as push-and-turn, squeeze-and-turn, pull-and-turn, or turn-and-push. While these opening requirements may successfully thwart youngsters, it was determined after implementation of the PPPA that they also were problematic for older Americans who lacked the strength or dexterity to use the packages properly. Wrote PD in July, 1995: "As a result, many either buy non-CR packages or simply leave the closures off the container."

Therefore, in 1995, CPSC amended the child-resistant packaging protocol, calling for test panels to be comprised of adults aged 50 to 70 instead of 18 to 45, as previously required. Noted the same PD article: "CPSC wants packagers to redesign caps so that consumers must rely more on cognitive skills rather than brute-strength opening." It added that CPSC had cited Procter & Gamble's Safety Squease™ squeeze-and-turn cap supplied by West Co. for its Scope mouthwash, introduced in 1994, as an excellent example.

The upshot of PPPA is that thousands of children have been protected from unintentionally ingesting harmful toxic substances. In a test conducted by CPSC in 1992, it determined that between 1964 and 1992, CR packaging had reduced the oral prescription medicine-related death rate by up to 1.4 deaths per million children under the age of five, which equates to about 24 fewer child deaths annually.

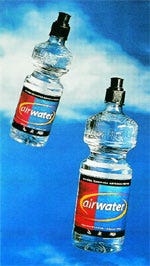

Sports drinks sport push-pull nozzles

Push-pull nozzles have been used for decades for household products and other special applications, but they made their first major foray into the food industry in the mid-'90s on bottles of sports drinks. This was soon followed by  use on the many brands of bottled water that hit the market. Users liked the closure because of its ease of use and resealability. It could be easily opened for a quick drink, and then resealed with a simple push. The elimination of a screw cap with its need for two-handed manipulation was particularly appealing to active consumers, such as hikers, bikers and back packers. Another feature of the push-pull cap was its dual system of tamper-evidence and tamper-resistance that eliminated both the need for an additional shrink-wrap sleeve around the cap, and the need to remove the primary closure to drink from the bottle.

use on the many brands of bottled water that hit the market. Users liked the closure because of its ease of use and resealability. It could be easily opened for a quick drink, and then resealed with a simple push. The elimination of a screw cap with its need for two-handed manipulation was particularly appealing to active consumers, such as hikers, bikers and back packers. Another feature of the push-pull cap was its dual system of tamper-evidence and tamper-resistance that eliminated both the need for an additional shrink-wrap sleeve around the cap, and the need to remove the primary closure to drink from the bottle.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like