Sustainable Food Packaging Made from Pomace

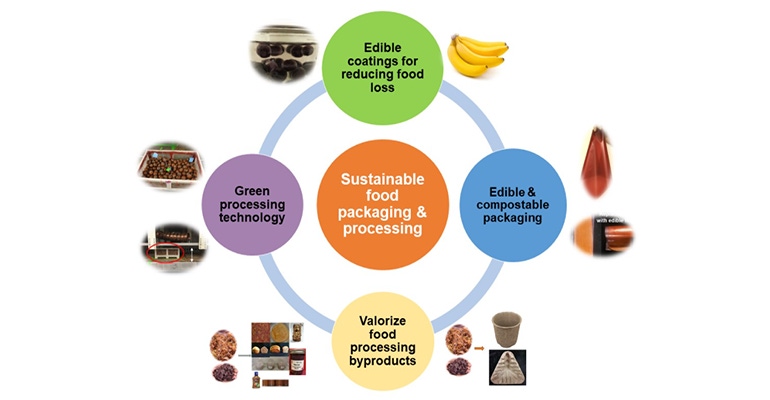

Researchers at Oregon State University convert juice pulp into edible films and compostable packaging to reduce food waste.

September 20, 2021

What if packaging that could dramatically reduce the environmentally impact was made from a food processing byproduct, pomace?

That’s one of the projects underway in the Sustainable Food Processing and Packaging Lab on the campus of Oregon State University under the direction of Yanyun Zhao, a professor in the Department of Food Science and Technology. With a doctorate in food engineering — she studied modified atmosphere packaging for her dissertation research — Zhao specializes in sustainable packaging development.

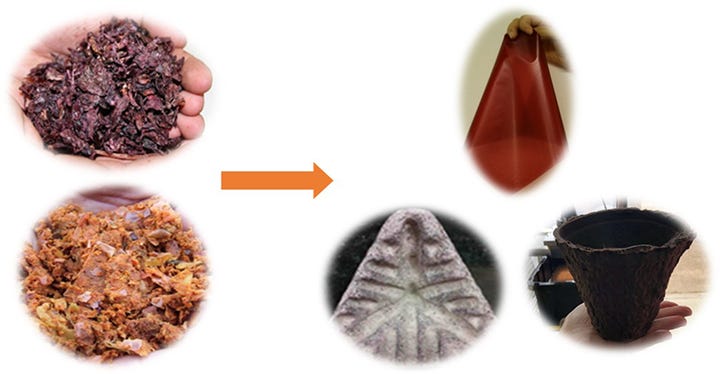

For several key projects under her direction, the base material is pomace, the pulpy byproduct that’s left after the juice of apples, wine grapes, and other fruit or vegetables is extracted. In one example, whole pomace is used to make compostable packaging. In another, pomace extract is used to produce edible films.

Pomace from fruit and wine grapes is an abundant resource of dietary fiber, phenolics, and other bioactive compounds, Zhao points out. While some companies have been extracting bioactive compounds from pomace, “there’s a huge amount of bulk material left…my research is aimed to use 100% of this fiber-rich byproduct to create eco-friendly packaging,” she tells Packaging Digest.

According to Zhao, fruit and vegetable pomace have high amount of phenolics, which provide good antioxidant and antimicrobial effects. Pomace-based edible films protect food products and provide additional antioxidant and antimicrobial benefits to packaged food.

While the research engages theoretical and fundamental studies, it also involves working closely with industry partners.

“It’s aimed at the commercial needs in the market and thus develops materials with specific functionality to meet targeted applications,” Zhao says.

The pomace is provided by local juice processors for free. “They’ve been highly supportive of our research,” she adds.

Edible fruit leather wrap film is made of cranberry pomace extract with natural cranberry juice color.

In other research, the lab produces edible films using food polymers to replace single-use plastic for foods. Some applications studied in Zhao’s lab include a single-use, edible-oil-and-seasonings pouch; an edible muffin liner (shown below); an edible wrap produced from pomace extract for fruit leather; and edible films that can be interleaved to wrap stacks of sliced cheese or meat for packaging.

In a parallel project, whole pomace is utilized to create compostable molded-pulp packaging products. That research has been underway for years with a granted patent, “but requires further research and development for creating packaging products to meet specific criteria of given food packaging applications,” Zhao notes.

Coatings for produce.

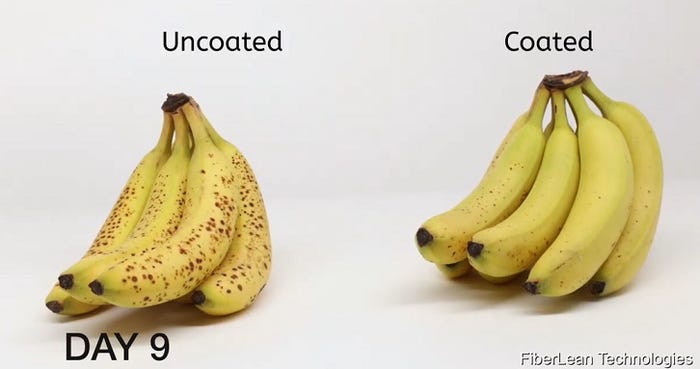

In addition, the lab has developed patented coating techniques for protecting and preserving food products, especially fruit crops across the supply chain. These coatings could potentially be a replacement for the wax coatings typically use for produce, for example, carnauba (derived from nature) or shellac. A video showing the shelf life of bananas with and without the coating can be seen here.

“In the United States today, about 52% of fruit and vegetables are lost, including 20% during production, and 15% during postharvest handling, storage, distribution, and retailing,” she points out. Zhao’s lab has developed novel food coatings to protect and preserve some fruit crops through the supply chain. The goal is creating a barrier to both oxygen and moisture, the enemies of the shelf life of fresh produce.

Zhao was invited to showcase the edible coating research at the USDA Food Loss and Waste Innovation Fair held May 26, 2021. She notes that “our research was right on target, especially for fresh fruits and vegetables.”

A major benefit of the coatings is that they perform as covert packaging versus using a plastic wrap that’s apparent to everyone include those who would view it as unnecessary over packaging. Coatings serve a similar function in a far more sustainable, natural way.

“The coating is like a skin-tight packaging when done with the right properties,” Zhao explains. “Also, an antimicrobial agent can be incorporated into the coatings and released during storage to further extend shelf life of a coated food item. This requires a good understanding of the coating itself as well as the physiological property of that specific food…a banana behaves a lot differently than a blueberry.”

The work is further complicated by the fact that ensuring the coating is applied efficiently involves studying the surface morphology of the produce.

Due to different applications with different functional requirements between coatings and films, the exact formulations can be different, which is being studied,” Zhao says.

There’s also the production efficiency improvement of applying a coating versus a packaging film applied using semiautomatic or automated film-wrapping equipment. Produce packers have been using coatings for years for citrus fruits, apples, and pears, that are applied by brushes followed by drying via a controlled-heat air tunnel or something similar.

All ingredients for the patented fruit coatings are Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) except for the fibrillated cellulose materials. “Studies on the safety of fibrillated cellulose are ongoing and application for GRAS petition of fibrillated cellulose is underway by our industrial licensee,” she says.

Zhao’s research has been financially supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) grant, the Oregon Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block grant, and industrial sponsors.

For now, Zhao will focus the R&D “on the coatings, edible films, and compostable packaging products to improve the performance of a given application and expand the applications of our sustainable packaging techniques to more food items.”

Zhao may be contacted through the OSU website.

You May Also Like