USP: 'It’s your product and you know the risk—you determine the testing'

July 7, 2016

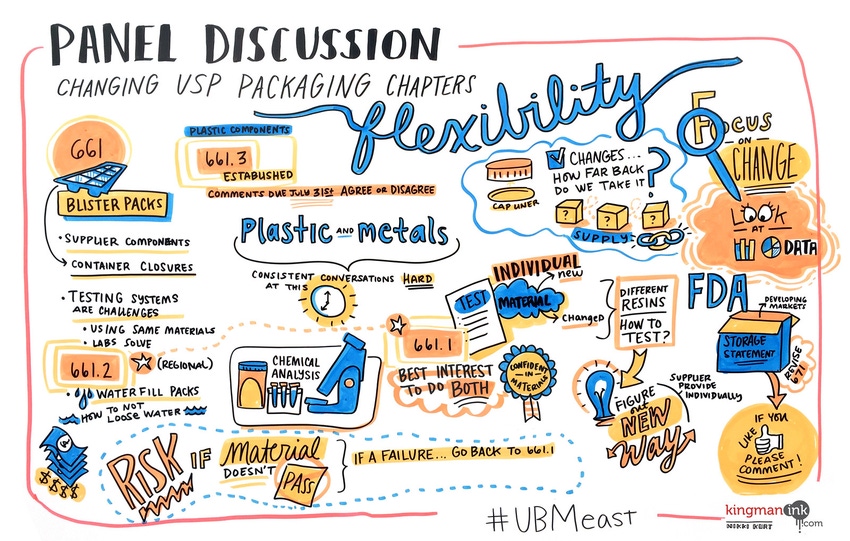

When the U.S. Pharmacopeia set out to modernize Chapter <661> Containers—Plastics, now known as <661> Plastic Packaging Systems and Their Materials of Construction, users wondered how much the revised standard would impact their testing programs. Attendees at the June 16 EastPack Pharmaceutical & Medical Packaging conference gained a better understanding of what’s expected of them—and how much freedom they really do have.

Desmond Hunt, PhD, USP’s Senior Scientific Liaison, spoke about the history and intent behind Chapter <661> and its two subchapters, <661.1> Plastic Materials of Construction and <661.2> Plastic Packaging Systems for Pharmaceuticals. After his presentation, he joined the panel discussion “Putting the Changing USP Packaging Chapters to Work” moderated by Dwain L. Sparks, Strategic Advisor & Expert Consultant, YourEncore (Eli Lilly & Co. Retiree). The panel also featured Dan Malinowski, Senior Director of Package Technology & Innovation, Pfizer; and Brandon Zurawlow, Associate Director of Container Qualification & CCIT, Whitehouse Laboratories, a division of AMRI.

Chapter <661>’s revision was needed, said Hunt, because its earlier “tests didn’t lead to data that would show whether a material was suitable or safe,” he said.

Hunt explained the testing activities outlined for various dosage forms under each subchapter and when such tests would be required. For instance, <661.1> covers physiochemical tests as well as tests for extractable metals and polymer additives for materials of construction, while <661.2> covers physiochemical tests and risk-based testing for extractables and leachables for packaging systems. Both subchapters outline requirements for in vitro testing (USP <87> and in vivo testing (USP <88>).

"Chapter <661> ties everything together,” said Hunt.

Hunt also discussed several applications for testing. New packaging systems that have not gained regulatory approval for use with a to-be-marketed pharmaceutical product would need to be tested according to <661.1> and <661.2>, he said. However, testing of packaging systems used with a currently marketed pharmaceutical product to be applied to a different pharmaceutical product would depend upon the dosage form and conditions of use according to the level of risk.

“We’re moving away from testing to test but [instead] to determine safety and suitability,” Hunt said.

“We’re constantly getting feedback from stakeholders,” he continued. “Please reach out to me and let me know. We are trying to work in more dynamic ways.”

During the panel discussion, panelists explored whether suppliers would be the ones to test individual materials of construction according to <661.1>, while drug manufacturers would test container closure systems to <661.2>.

Malinowski said that “it would be great if a supplier could precertify a material to <661.1>. It gives us confidence. Because if it doesn’t pass <661.2>, do drug companies have to go back and test, and if so, what materials?”

“We’re hearing interplay between suppliers and [drug] manufacturers,” said Zurawlow, whose testing lab performs such tests for companies on a contract basis.

“Some manufacturers may want to test their particular product to <661.1>,” observed Malinowski.

“That example is at the heart of why the chapter is divided up,” said Hunt.

“What about the middle layer of a blister film?” asked Sparks. “Should it be tested if viable?”

Georgia Mohr, Marketing Director - Pharmaceuticals for Bemis Healthcare, which provides blister film structures, said from the audience that “we support drug contact layer testing, but also materials of construction so there’s a level of comfort.”

“But the chapter says <661.1> [is] not packaging systems, just individual plastic layers,” noted Zurawlow.

Mike Reiter from Perrigo, an EastPack speaker who would later be participating in the afternoon panel discussion on PROTECT, asked from the audience: “In regards to colorants added to bottles or when a supplier uses a new carrier resin—when we’re looking at that minutia, what does one do? How far back do you realistically take it?”

"The key is that the supplier updates their DMF and tests to <661.1>,” advised Malinowski.

“If there’s not a method suitable in the compendia, it is up to the user,” said Hunt.

The panel also examined some of the challenges surrounding the testing of blister packaging systems.

For instance, Zurawlow asked, “how do you get water filled and sealed blisters?”

“Could you use an alternate test?” asked a member of the audience.

“There is language for an alternate method” in the chapter, noted Sparks.

"We’ll have dialogue—if Brandon has a robust method, we could include it,” said Hunt, adding that approaches are “evolving.”

“We could take the whole package system,” said Zurawlow. He later explained to PMP News that “by ‘take the whole package system,’ the context was to take the whole package system and submerge it in water similar to the old approach for <661>, rather than fill cavities with water. This, however, would introduce unintended variables to the test—such as direct water contact with external components, such as blister lidding coated with a printed paper.”

When discussing <661.2>, Hunt explained that testing essentially generates a “chemical safety assessment of a packaging system, based on risk-based testing,” he said. However, “if you have data to support not doing extensive chemical testing, you don’t have to.

“It’s your product and you know the risk—you determine the testing,” he added. In terms of risk to product and material, “figure out what testing is appropriate with the confines of the chapter.”

“Don’t expect transformational change,” said Malinowski. “Between manufacturers and agencies, determine what is needed based on sensitivity.”

USP <661> isn’t the only chapter changing. Currently being revised is <381> Elastomeric Closures for Injections. “We are modernizing the chapter first,” Hunt said at EastPack. It will also have a subchapter for orally inhaled products and the guidance chapter <1381>. A Workshop will be held next June that will discuss the rationale for the revision of <381> and <660> Containers−Glass, he told PMP News after the event.

A metal packaging chapter is also underway (<662> Metal Packaging Components and Systems for Pharmaceutical Use).

Sparks also asked Hunt about the status of the drug product monograph storage statements, particularly the instruction to store drug products in a “tight container.” Hunt described efforts proposing to remove the packaging storage statements referring to “tight containers” and “well closed” from drug product and drug substance monographs, which could number as high as 4000 monographs. (The effort will be discussed in a Stimuli Article in PF 42 (4) July 2016.)

And USP <671> is up next for revision. Hunt told PMP News that “the next revision will work to make it clear what tests are required for the various users of the chapter.”

Hunt explained during the conference that USP is “trying to get our packaging chapters revised before FDA revises its packaging chapter,” referring to FDA’s guidance, “Container Closure Systems for Packaging Human Drugs and Biologics.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like