4 countries generate about half the plastic marine debris

The problem of ocean debris is like the game of “Dirty Backyard.” The amount of plastic pollution in our oceans continues to increase, with countries in rapidly developing economies in Southwest Asia being the largest contributors. What can we do to reverse this trend and clean up our seas?

Did you ever play “Dirty Backyard” as a kid in gym class? The class was divided by a volleyball net and buckets of foam balls were unloaded onto the court. You had a minute to throw as many balls from your side to the other while foam balls were raining down on you. The team that had the least balls littering their side of the court at the end of the minute was declared the winner, having successfully cleaned their dirty backyard. I find the problem of ocean debris leakage like the game of Dirty Backyard; out of sight, out of mind. Unfortunately, the oceans are all of our backyards, and they are dirty.

A 2010 study on plastic marine debris, which I referenced in a 2013 article on the same topic, concluded, “Despite a rapid increase in plastic production and disposal during this time [1986-2008], no trend in plastic concentration was observed in the region of highest accumulation.” Results of the study were published in the September 2010 issue of Science magazine. The article, “Plastic Accumulation in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre,” was written by Kara Lavender Law, et. al.

I was thrilled by this scientific finding that while plastic production and consumption continues to increase, plastic pollution in the oceans has not. After all, up until the Ocean Dumping Act (1972), U.S. marine waters were a “convenient alternative to land-based sites for the disposal of various wastes such as sewage sludge, industrial wastes and pipeline discharges and runoff.” It should come as no surprise, I reasoned, that plastic marine debris is simply the result of this “out of sight, out of mind” colloquialism.

Then I attended the SustPack 2015 conference in Orlando this March, where I heard a presentation titled “Confronting Ocean Plastic Pollution at the Global Level” from the director of the Trash Free Sea Program at the Ocean Conservancy, Nicholas Mallos. While a portion of ocean plastic pollution comes from ocean-based inputs like illegal dumping and lost fishing equipment, according to Mallos, the majority of it (approximately 80%) comes from land-based sources, taking the form of packaging such as bags, bottles, closures and foodservice containers.

He cited a 2015 study that finds land-based “plastic leakage” into the ocean is not only increasing year after year, but the largest quantities are coming from a small number of rapidly developing countries. These countries, listed from highest to lowest contributor are: China, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam; together representing a concentration of almost half of plastic pollution entering the ocean. #Mindblown.

For Mallos, collaborative, comprehensive and holistic approaches to plastic leakage mitigation strategies will be based on sound science and dependent on the unique geo-political and socio-economic realities of the country.

He discusses the implications of this latest study on ocean debris rhetoric and plastics leakage mitigation strategies in this exclusive interview.

Do you believe that where the plastic is produced (geographically) has any impact on where and how it ends up on the ocean?

Mallos: The largest input of plastic into the ocean occurs where it is being consumed and disposed of.…Through efforts like Operation Clean Sweep, the loss of resin pellets at the manufacturing level has been reduced greatly, so where plastic is being produced is less of a factor than the final destination of where the plastic is going.

In your presentation, you showed that 49% of plastic leakage to ocean comes from China, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam. What do these countries share that makes them the largest contributors to ocean debris? How can we understand this trend between developing countries and plastic leakage to the ocean?

Mallos: This is a problem associated with development and insufficient capacity. An increasing middle class in these countries has increased purchasing power and consumption. The capacity to collect and manage [waste]—including plastic—has not kept up with the pace of development. The U.S. faced similar challenges in the past, which is why we implemented many of the waste management systems that exist today. If we look 10 years into the future, many countries in Africa will likely experience the same challenges.

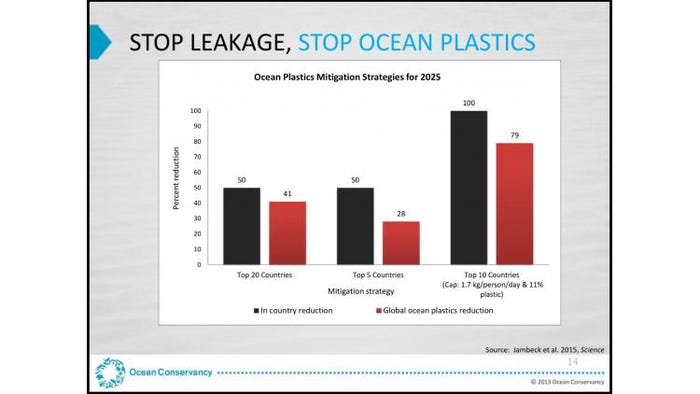

Can you expand on the “Ocean Plastics Mitigation Strategies for 2025” slide from your presentation (shown above)? What do the “top 20 countries vs. top 5 countries” mean?

Mallos: If you can mitigate, control and improve the amount of mismanaged waste among the largest contributors, like China and Indonesia, then you can reduce the amount of debris entering the ocean. Ocean Conservancy is working with industry and the NGO [non-governmental organization] community to understand the underlying incentives and economics of the countries contributing the most debris into the ocean to determine the most appropriate solutions to put in place to really tackle this issue. There are a range of solutions here and they won’t all work for every geography. We must engage with people on the ground, as they are the ones to oversee and implement the mitigation strategies deemed appropriate.”

According to the study, “Reducing the amount of mismanaged waste by 50% in these top 20 countries would result in a nearly 40% decline in global inputs of plastic to the ocean.”

In your presentation, you claimed that a “systemic solution is needed;” that is, “Industry, in collaboration with civil society and governments, must play a leadership role in identifying, financing and implementing locally-appropriate waste management systems and strategies.” Are you advocating an extended producer responsibility (EPR) scheme?

Mallos: The issue of waste management and ocean plastic leakage is on the radar of governments in many of the top contributing nations, but not always at the top of the list. Issues like human health, food security and access to water take priority in many of these rapidly developing countries, and there is simply not enough money to fund every high-priority project.

Industry has a responsibility, in conjunction with other organizations, to come together and change the underlying factors to make gathering and separating waste more viable. The issue with EPR is that it enhances recycling and recovery, but in many of the high-contributing geographies, basic waste management systems don't exist. Whatever scenario is proposed, it will be a combination of factors. Collection and aggregation of materials is at the core of any solution.

Chandler Slavin is the sustainability coordinator and marketing manager at custom thermoforming company Dordan Manufacturing. Privately held and family owned and operated since 1962, Dordan is an engineering-based designer and manufacturer of plastic clamshells, blisters, trays and thermoformed components. Follow Slavin on Twitter @DordanMfg.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like