Here, there, everywhere: Global differences in sustainable packaging

October 11, 2018

After two trips to Asia, North American-based sustainability expert Bob Lilienfeld draws interesting conclusions about the cultural and socio-economic aspects of sustainability and packaging in different areas of the world.

In February 2018, I wrote for Packaging Digest about my Indonesia trip, visiting Asia Pulp & Paper’s offices in Jakarta and paper mill on Sumatra. I’ve just returned from a similar visit to China, touring APP’s offices in Shanghai, along with its mills near the city of Ningbo and on the island of Hainan. I was told that the latter mill is the largest in the world, capable of turning pulp into 10-meter-wide, 90 ton rolls of paper in 45 minutes (see photo above).

While I was prepared to once again hear about the value of APP’s low-cost advantage through vertical integration and highly automated paperboard production, I was not prepared for the key piece of learning from the Chinese experience: Approaches to, and beliefs about, sustainability are fairly different in China than in Indonesia, and vastly different versus North America. The differences reflect the economic, social and environmental issues, and values, of each country’s cultures and communities.

Unlike Indonesia, which contains vast stretches of tropical rainforests and plantations, the economically accessible forests near China’s primary transportation and population centers have been largely depleted: Much of the pulp processed in APP’s China paper mills is trans-shipped from its Indonesian pulp mills, and woodchips used for pulp making are imported from other sources and locations. (I was told that the chips I saw offloaded via container ships at the Hainan mill were certified to be sustainably sourced in Vietnam.)

The small amount of available plantation land in China must therefore be carefully managed for sustainability. Here are two examples of APP’s approach to sustainable forestry:

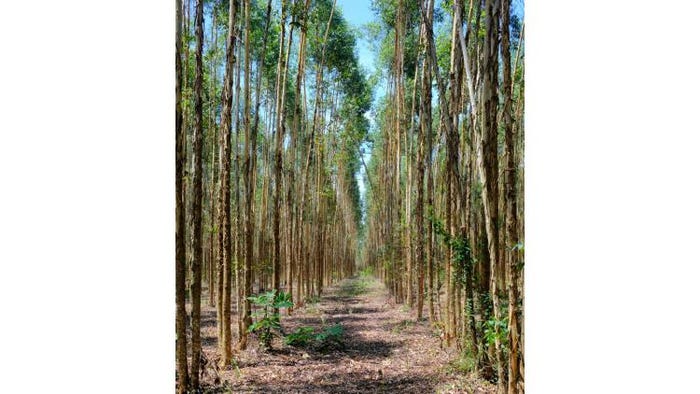

To maximize economic efficiency and minimize the environmental impact of pulp production, APP practices coppicing, a method of woodland management that exploits the capacity of certain tree species (in this case acacia) to grow new shoots from stumps after cutting. The two or three strongest shoots are chosen, and the others trimmed off.

Note in the photo that all of the trees are actually two or three trees growing from a single stump. This practice at least doubles the yield per stump (and thus per hectare of land), which significantly enhances economics while reducing the need (or temptation) to increase plantation size.

From a social perspective, woodlands are shared with local farmers, who use them to provide food and shelter for themselves and their livestock—in this case, chickens! (I’m sure the poultry return the favor by helping to fertilize the trees.)

Here’s another example of a local approach to sustainability, and one that would not be considered as such here in the United States: When I asked APP personnel how much of their (and other producers’) paperboard and corrugated is being recycled, they proudly told me “100%.” Incredulous, I asked how that could be, and was told that in rural areas, it was collected and burned for fuel.

Even though this meant that individual families’ combined burning activities amounted to significant local air pollution, it was felt that this was a more sustainable strategy than chopping down even more trees for wood-fired heating and cooking. By the way, this practice was quite evident, as we saw multiple small fires burning in local fields and near homes when travelling between Shanghai and Ningbo, and throughout the rural areas of Hainan.

Even in big cities, much of the collection for recycling is handled by local entrepreneurs, rather than by government-funded collection programs. (In the photo, note the care in containing and protecting the recovered board, here on one of Shanghai’s privately owned and operated “collection trucks.”)

And, while we here in North America believe coal to be the fuel of last resort, APP was very proud of its coal-fired plants, which also powered local communities that might not otherwise have access to electricity. When I explained this difference in thinking to one of the plant managers, he said, “We constantly update these power stations to minimize greenhouse gas generation and pollution. And, we really don’t have other significant energy sources near many of our Chinese plants. It’s also the right thing to do for rural communities that would otherwise remain way behind in terms of living standards. Isn’t that a big part of sustainability?”

That’s a great question, and leads to the ultimate sustainability conundrum: Globally, what is it we’re all trying to accomplish via our various, and at times vastly different, approaches to waste prevention and remediation? Is it actually possible to enhance overall quality of life without creating massive environmental degradation in the air, on land and at sea?

Looked at from this perspective, packaging by itself isn’t that big of an environmental issue, is it? In fact, I’ll bet it’s primarily a symptom, and not the actual disease.

The disease, if you will, is the multiplicative effect of consumption and population growth. I would argue that packaging may facilitate this growth, but it certainly is not responsible for it. Thus, if we’re not willing to admit to and tackle the negative impacts of our basic human desires, we do not have the collective will to truly solve the problems they are creating.

Of course the packaging industry has a role to play, and work to do, when it comes to providing economic, environmental and social sustainability. But, let’s be honest with ourselves and start reminding regulators, lawmakers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the media and the public that it’s a supporting role, not a starring one. Bans on straws, bags and cups here in North America are not going to mitigate climate change, reduce food waste or clean up the oceans.

True sustainability must transcend cultural and socio-economic differences, with specific broad scale goals set over specific time periods designed to mitigate specific problems. It will require significant behavior change from each of us here in North America, as well as from all of us around the world.

Robert (Bob) Lilienfeld has been involved with sustainable packaging for more than 20 years. He is currently editor and publisher of The ULS (Use Less Stuff) Report, a marketing and communications consultant and a professional photographer.

********************************************************************************

Packaging solutions come to Minneapolis: As part of the region’s largest advanced design and manufacturing event, MinnPack 2018—and the five related shows taking place alongside it—brings 500+ suppliers, 5,000+ peers and 60+ hours of education together under one roof. Register for free today.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like