New plastic discovered: Solution to pollution?

Plastic packaging pundit Chandler Slavin comments on a new “infinitely recyclable” plastic that redefines the economics of packaging recycling. Poly(diketoenamine) or PDK could offer a solution to waste and pollution in the oceans.

Environmental dread, that pang you feel in your chest when you read another story about the decay of our natural environment. Plastics pollution in particular, a magnifying glass through which we see our over-consumptive, throwaway society.

Plastic packaging has long been the scapegoat of our collective environmental anxiety: We touch it, we recycle it—yet it persists in our natural environment. This is because there is no easy money in recycling. With the exception of aluminum cans, plastic bottles, and uncoated corrugate, most post-consumer packaging isn’t recycled domestically because the cost of collection, sortation, and reprocessing outweighs the value of the recovered material. Many municipalities have stopped collecting glass for this reason; and mixed paper, previously sent to China for reprocessing before its import ban, no longer has a home.

Prior to China’s ban on recovered-material imports, the low cost of manual separation, married with the lack of environmental regulations and waste management accountability, long provided an end market for America’s “recyclables:” Reused, recycled, buried or burned, the value of the material was at best degraded, and most likely, lost. With these rapidly developing countries—China, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam—generating nearly 60% of all plastics entering the ocean each year, plastics pollution results largely from poor waste management in the same countries that America is sending its waste to.

This is the foundation of the plastics pollution problem today. If there is no post-use value to motivate its collection for recovery, then plastics will continue to be disposed of irresponsibly.

Plastics, due to their lightweight and versatile nature, offer shipping efficiencies, food preservation and product protection. The environmental costs of producing food and products far exceed that of the packaging that protects it. Yet plastic packaging is seen as cheap and disposable. How do you internalize the environmental value of plastics so that it is seen as worthy of recovery?

Natural capital accounting firm, TruCost, quantifies the environmental costs of products over their lifecycle: It finds that if plastics were replaced with alternative materials, like paper, glass, or aluminum, then the net environmental cost would be at a factor of 4:1. This means that you would need roughly four times the amount of alternative material to achieve the same function as plastics. This need to up gage for material substitutions has significant ramifications on the environmental cost of the packaging over its lifecycle.

Unfortunately, natural capital accounting is in its infancy: Policy or shareholders don’t manage these costs. Thus, the environmental burden of the products and services that we consume today will be carried on the backs of future generations.

Bans on single-use disposable plastic packaging attempt to slow the tide of plastics pollution. Commitments to reduction from consumer brands hope for the same. Yet these efforts dismiss the environmental repercussions of material substitutions, while neglecting to address the systemic causes of plastics pollution. Targeting the symptom instead of the disease, we focus on the low-hanging fruit of sustainability, discouraging innovation.

If we engineered the plastics pollution problem, then why can’t we engineer the solution?

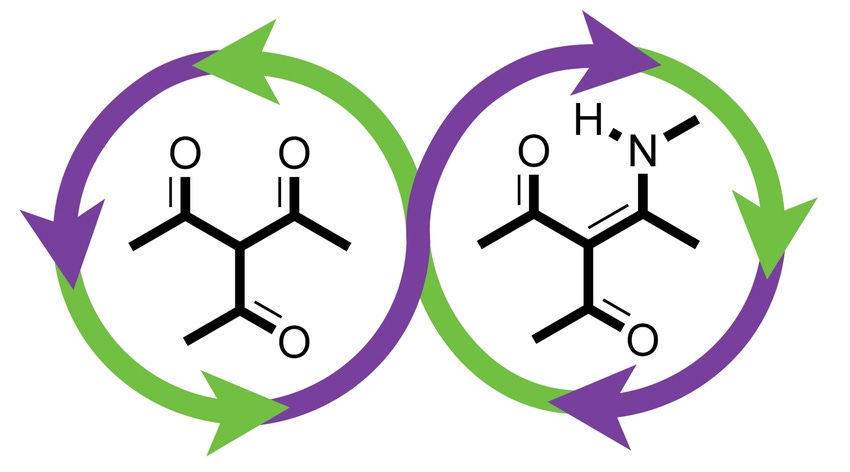

On April 22, scientists at Berkeley Labs published a report in the journal Nature Chemistry that made global headlines. Titled Closed-loop recycling of plastics enabled by dynamic covalent diketoenamine bonds, the report discusses the discovery of a new plastic, poly(diketoenamine) or PDK, that can facilitate a circular economy for plastic. PDK can be recycled over and over again without compromising its quality, and therefore, maintains its value post-use.

Peter Christensen, a postdoctoral researcher at Berkeley Labs, and staff scientist, Brett Helms, together with co-authors Angelique Scheuermann and Kathryn Loeffler, discovered a way to build plastics with recyclability as the foundation of its molecular constitution.

This time-lapse video shows a piece of PDK plastic in acid as it degrades to its molecular building blocks—monomers. The acid helps to break the bonds between the monomers and separate them from the chemical additives that give plastic its look and feel. (Credit: Peter Christensen/ Berkeley Lab)

By replacing the stubborn chemical bonds of traditional plastics with “reversible bonds,” the original monomers of PDK can be recovered by being submerged in a highly acidic solution. These recovered monomers can then be made into a host of different plastics while maintaining their “virgin” quality over cycles of use. Many plastics—because of the multitude of types produced (such as colored, rigid, flexible or multi-composite materials)—are hard to recycle via conventional methods, because the challenge of sortation and reprocessing at the municipal level. “Lookalike” plastics get reprocessed together as a low-grade plastics mix, the end markets to which are often limited and without economic value.

The ease of recycling PDK back to its original quality and without the need for expensive recycling technologies is a breakthrough for the economically viable recovery of plastics.

The authors conclude:

“Recovered monomers can be re-manufactured into the same polymer…without loss of performance…the ease with which [PDK] can be manufactured, used, recycled and re-used—without losing value—points to new directions in designing sustainable polymers with minimal environmental impact.”

Plastics, historically trapped in the linear economic model of production, use and disposal, have the opportunity to participate in the circular economy as demonstrated with the discovery of PDK. Modeled after the regenerative framework of nature, the circular economy creates no waste because all system inputs produce equally valuable outputs.

PDK demonstrates how innovations spurred by human ingenuity can redefine our relationship with plastics. A concrete manifestation of The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s “New Plastics Economy,” PDK offers hope.

We have the opportunity to change our perception of plastics: Not as something that is cheap and disposable, but something that is valuable, something to be saved. In viewing problems like plastics pollution with a magnifying glass, we neglect the panoramic view. Only in seeing the big picture can innovation occur, and only with innovation can we transcend.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like