The sustainability of ecommerce packaging is in question

Does ecommerce generate more packaging waste than traditional retail distribution? With ecommerce sales growing in the U.S. at 14.6% in 2015, according to Internet Retailer, it’s time for some answers. A new whitepaper by environmental and policy packaging group Ameripen brings clarity to the murky topic of sustainability for ecommerce packaging and identifies five opportunities for improvements.

Published in January 2017, Ameripen’s free 15-page whitepaper “Optimizing Packaging for an E-commerce World” succinctly outlines the unique sustainability challenges for packaging in the ecommerce channel. The conclusion? “[O]ptimizing packaging for ecommerce may very well look different than design for traditional retail, due to the different demands of the respective distribution chains.

“Opportunities to invest in further development of the packaging supply chain for e-commerce and subsequently omni-commerce scan the breadth of distribution channel and solutions will come only through industry collaboration and transparency.”

Authors Bob Lilienfeld, Ameripen senior communications director, and Kyla Fisher, founder, Three Peaks Sustainability, explain why this topic deserves attention now and how packaging designers will adapt.

Bob Lilienfeld

Kyla Fisher

Do brand owners need to worry about ecommerce packaging or is this the job of the fulfillment house?

Lilienfeld: Both. Consumers don’t necessarily differentiate between the retailer or the brand. We know consumers believe that packaging is reflective of company’s sustainability commitment, so brands and retailers both need to ensure their packaging demonstrates this commitment.

What surprised you the most as you were researching ecommerce packaging to write this whitepaper and why?

Lilienfeld: I was most surprised by the lack of big picture thinking—the inability to see product protection and damage control as a major sustainability benefit of packaging. There’s some available data related to product damage, but other than a few academics, the industry is not fully discussing the fact that you must look at the economic, environmental and social impact of both the product and the packaging, including the primary, cushioning and transport components.

Fisher: There’s also widespread belief and acceptance that ecommerce is driving increased packaging. A common refrain we hear is that ecommerce packaging is excessive (and there are certainly examples of that) but when we look across the value chain and how the three systems of packaging (primary, secondary and tertiary) are shifting, it left us wondering if we are cumulatively using more material or if the disposal of packaging has simply shifted from retailers to consumers. This needs more study as it could have a significant impact on future packaging and waste policy and strategies.

After all your research, would you say that direct-to-consumer distribution is more wasteful from an environmental perspective—using more materials and energy, and generating more waste—than typical retail distribution? Why or why not?

Lilienfeld: We found conflicting studies that pointed in either direction—depending on who did the research, where they stood in the value chain and/or distribution channel, what products were evaluated and what consumer behaviors were measured. There are simply too many variables to create an all-encompassing life-cycle analysis (LCA). And frankly, when the differences by product, application, distance, weight and cost are factored in, the answer is going to be “It depends.”

The whitepaper points out major differences between ecommerce and traditional retail sales: Ecommerce purchases delivered directly to consumers…

• require more “touchpoints”

• pose a higher risk of damage

• tend to result in significantly higher return rates

One solution might be more durable packages. Does this necessarily mean using more material and, thus, being less sustainable?

Lilienfeld: Again, we can’t look at the concept of sustainability in a vacuum. We must look at the entire system of product containment, protection, storage, delivery and end-of-life. For example, a package made of 100% recycled, compostable paper and biopolymers may appear to be sustainable, but if a more traditional packaging configuration means that my 70-inch, $2,000 4K TV shows up in my house in perfect condition, the second is more sustainable from a big picture perspective—which is the one that drives potential environmental impacts.

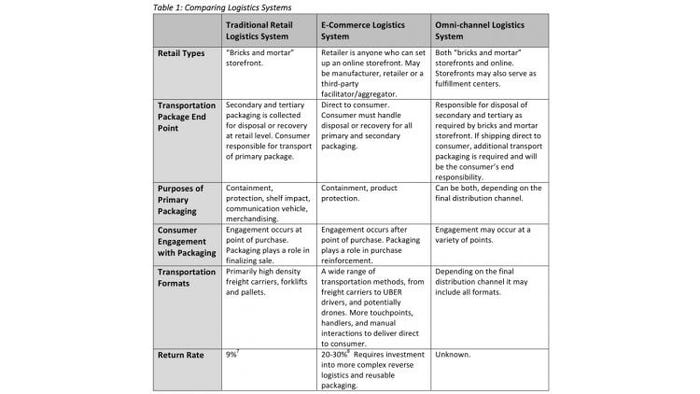

Table 1 charts six differences between traditional retail, ecommerce and omni-channel logistics. How difficult was this table to put together?

Fisher: It was surprising to us that there aren’t more comparisons publicly available. The data was easy to access and only touches on broad aspects. It would be interesting to develop it further to analyze aspects like damage rates and cumulative material demand in each channel. It’s imperative that we begin to understand if total volume is increasing, or simply shifting between the retailer and consumer.

Ecommerce return rates are between 20% and 30%, which is more than double the 9% traditional retail return rate. That’s one reason ecommerce packaging carries such a heavy burden for product protection—it often is also used for reverse logistics. Additionally, there is more opportunity for product damage for direct-to-consumer shipments because of the high number of touchpoints. What should packaging professionals keep top of mind when designing and testing protective packaging for ecommerce distribution and why?

Fisher: After exploring the difference in the distribution channels, the paper explores consumer expectations as they relate to ecommerce. This is key to where designers should focus.

When you break down the return rate, there are certain products with higher return rates. Designers of those should consider the designing for return. But an interesting challenge with returnable packaging is excessive material. If 70% to 80% of product is not being returned and yet we are including a returnable label and possibly a new package for returns, then are we cumulatively creating more waste? There are ways around this, such as using printable labels or reusable packaging which serves for receipt and return—but designers will need to balance this with consumer ease.

Another area to explore further in design is the opportunity to design packaging specific to ecommerce where the primary package could be developed uniquely for shipping thereby eliminating secondary and tertiary packaging. This is an emerging market—Amazon is encouraging it somewhat with its frustration-free packaging but it’s not a mainstream practice.

And this approach isn’t without its challenges, including:

• costs of developing different stock-keeping units (SKUs) for each channel;

• how to address SKU’s for omni-commerce sales where the storefront could serve as either a warehouse from which material is shipped direct to the consumer or as a pickup location; and

• establishing alignment with consumer expectation: Consumers are accustomed to receiving the same package they would see online or choose from a storefront.

Also, while this is not directly related to returnable packaging, one area to consider is the emergence of dim weight pricing now used by most carriers. Dim weight factors both size and weight into shipping costs. Therefore, there is a trend toward lighter weight and decreased shipping volumes.

Partially in response to this, as well as consumer interest in recyclable and renewable materials, we’re seeing the emergence of new materials such as molded pulp, jute and films. As these materials enter the mainstream, anticipating and responding to them will be key to recovery. This is something both designers and recyclers will need to collaborate on.

How can there be best practices in ecommerce packaging when the products—and the variety of multiple products—in a single shipment can be so different?

Fisher: Multiple products in a shipment are referred to as “the basket.” Some suppliers use this approach to ensure that they minimize shipping costs by incentivizing the purchase of multiple items—similar to “upselling.” Yet as it relates to addressing “basket” orders, a challenge that needs to be explored is how to work with the “hub-and-spoke” model. If I order a basket of three goods, but they’re stored in three different fulfillment centers, the ability to collectively ship is not available. This frustrates consumers who don’t see that logistical challenge. Evaluating better how companies that develop basket incentives are addressing this might uncover some best practices for further exploration.

In terms of ecommerce packaging at large, the bigger challenge right now is obtaining access to data on damage rates by material and/or format. Most of this is currently proprietary. Opening up data through industry associations and third parties would help better inform as well as educate the general consumer on why ecommerce packaging may shift from what they have traditionally found in a storefront.

The whitepaper touches on new safety concerns that will need to be addressed, such as delivery people handling heavy items and ensuring the safe distribution of fresh foods. Who will be or should be setting safety standards for ecommerce packaging?

Fisher: The International Safe Transit Assoc. (ISTA) appears to be leading these efforts. Historically, distribution safety has been its domain, but ecommerce is a unique animal and we believe collaboration across associations will be needed.

There are also other organizations engaged in these dialogues. The Sustainable Packaging Coalition has a cold chain value committee that is looking at packaging for the safe distribution of fresh food. The Grocery Manufacturers Assn. has also commissioned studies in this area.

*******************************************************************************

Learn what it takes to innovate in the packaging space at the new Advanced Design & Manufacturing Cleveland event (Mar. 29-30; Cleveland, OH). Register today!

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like