Eyes on the skies: The dream of drone delivery starts to take flight

Drone package delivery is sparking the imagination of retailers, consumers and everybody in between. Here’s what it means to packaging professionals.

Amazon, Google, DHL and Walmart are all working on the supply chain of tomorrow, including package handling and delivery. And although the future looks somewhat different to each of them, all four know they want aerial drone technology to be part of it.

Driving their interest in drone package delivery is the possibility of super-fast shipping—as in next half-hour rather than next day—which in turn relates to the growth of e-commerce and consumers’ changing expectations for what constitutes timely delivery.

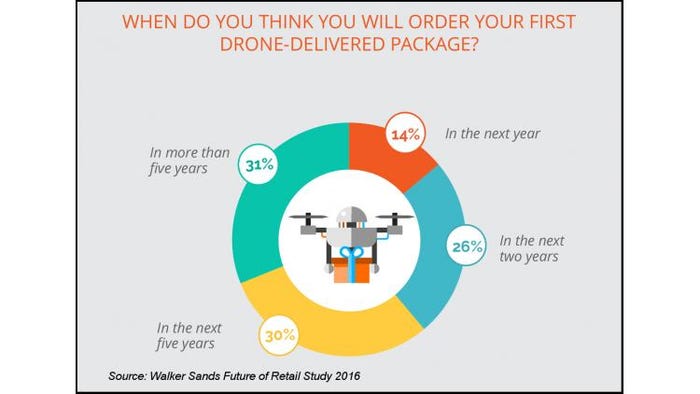

Online shoppers clearly are interested in getting their purchases as quickly as possible. In a 2016 survey conducted by Walker Sands Communications, 79% of respondents said they would be “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to request drone delivery of their package if it could be delivered within an hour. Of the 1,433 U.S. consumers surveyed, 26% expected to order their first drone-delivered package “in the next two years,” and another 30% said “in the next five years.”

In addition, 73% of Walker Sands’ survey participants said they would pay up to $10 for a drone delivery. Although the economics of drone delivery have not yet been worked out, robust delivery fees could help offset operating costs.

Immediately, if not sooner

Minimizing the time it takes to get products from a warehouse to consumers is a key benefit of drone delivery for e-commerce companies. Amazon has publicly stated that the goal of its Prime Air service, which will use aerial drones, is to get packages to customers in 30 minutes or less—on-demand delivery, essentially.

Amazon Prime Air has tested drone prototypes designed with, for example, a small cargo bay or an external bin for carrying packages. In all cases, the packages loaded onto Amazon’s drones are on the small side, weighing no more than five pounds; the drones would be able to fly 10 miles or more to make a delivery.

The company reportedly has been testing its drones in Canada, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Amazon declined to comment for this article.

Amazon Prime Air, still in development, is a system for drone delivery of packages weighing up to five pounds within 30 minutes or less.

Separately, DHL has been testing drones for the delivery of express and emergency items and/or deliveries to difficult-to-reach areas, such as islands and mountaintops. The company completed a three-month test of its Parcelcopter 3.0, a tilt-wing aerial vehicle, in the Bavarian Alps in early 2016.

The test incorporated DHL’s automated Skyport cargo loading and unloading system. Local customers who wished to send a package by drone between the trial program’s two stations simply inserted their package into the Skyport, and the item was loaded onto the drone. Most of the packages contained sporting goods or medicine.

Google, though its Project Wing program, also has been testing drones. One of Google’s delivery models combines aerial drones with rolling, earthbound robots—the aerial vehicles transfer packages to the robots on the ground (also see “Down-to-earth drones tackle the ‘last mile’”). The company previously had tested a drone that lowered packages, on a tether, directly to the ground. Google, which has shied away from publicity about Project Wing, had no comment.

******************************************************************************

Download your free copy of Packaging Digest’s 2016 Drone Package Delivery report, a 40-page PDF of results from our exclusive research on this emerging technology. CLICK HERE NOW.

******************************************************************************

In the retail arena, Walmart made news in late 2015 when it asked the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for an exemption to the rules then in effect, which prohibited the use of drones for commercial purposes. Walmart expressed interest in using drones for inventory management and possibly for curbside and home delivery.

Walmart currently is testing drones for stock checking at a Bentonville, AR, distribution center. The drones fly methodically through the distribution center’s aisles, taking digital images of product tracking numbers. The goal is to identify any items that are stored in the wrong place, so they can be moved. Walmart could roll the technology out as soon as December 2016.

Walmart is testing the use of drones to keep package inventories in line at its Bentonville distribution center. (Stock photo is not showing Walmart’s actual use.)

Getting the serum to the baby

In addition to delivering items quickly, drones can serve difficult-to-access areas better than conventional delivery vehicles.

“FedEx has expressed some interest in this ‘last mile,’ where if you’re sending a truck out, it’s got to go way out of the way on curvy, windy roads to reach a destination. Drones might be viable for those things,” says Frank Ketcham, founder and CEO of San Francisco-based Senord Technologies, which uses aerial drones to inspect property and infrastructure.

“What is it that a bike messenger can’t do, a delivery truck can’t do, FedEx can’t do? What is it that we need not in four hours but in 45 minutes?” Ketcham asks, noting that those are the items for which drone delivery make sense.

An item delivered by drone “has to be small. It has to be light. And it has to be extremely important,” Ketcham says. “There’s a very small segment where delivering by drone really makes sense. It’s getting medications to people that are in remote areas—getting the serum to the dying baby.”

In fact, using drones for disaster relief and the delivery of medicines and other healthcare supplies to remote or undeveloped areas is a lively area of research. For these applications, drones offer the benefits of fast delivery and the ability to reach areas that are isolated geographically or whose roads have been damaged.

Flirtey, a drone-delivery startup based in Reno, NV, has successfully completed several successful demonstrations of drone delivery for medical items. This summer, the company worked with Johns Hopkins to transport medical supplies and bio-samples between a location on land in New Jersey and an offshore barge.

A few months earlier, Flirtey accomplished what it characterizes as the first fully autonomous, FAA-approved urban drone delivery within the United States. That drone delivered a package containing a first-aid kit, water and food to a residential location in Hawthorne, NV. In a groundbreaking 2015 flight billed as the first U.S. drone delivery approved by the FAA, Flirtey successfully delivered medical supplies to a rural clinic in Virginia.

Flirtey worked with NASA’s Langley Research Center to make the first FAA-approved drone delivery within the United States. The cargo was medical supplies; the drone made the delivery to a clinic in rural Virginia in 2015.

The company’s six-rotor drone makes a delivery by carefully lowering the package, on a tether, to the ground as the drone hovers above the delivery zone. When the package is safely on the ground, the tether is pulled back to the drone, which then departs.

Flirtey sees a future for delivering commercial packages as well as medical and relief supplies via drones.“Our vision is to reinvent the delivery process” not only for e-commerce but also for food delivery and humanitarian projects, says Matt Sweeny, Flirtey’s CEO.

The rules of the sky

These intriguing drone-delivery demonstrations have led some to envision a sky buzzing with drones, each carrying a package addressed to a different location. But much work remains before such a scenario would be safe for people, animals and property on the ground; for other aircraft and birds; and even for the drones themselves.

Creating an air-traffic management system for drones—surveillance, in other words—is one of the first and most important things to accomplish. “You need some sort of surveillance for drones,” says Senord’s Ketcham, who is also a pilot with a leading U.S. carrier and a strategic advisor to the CalUnmanned Aviation Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley. “You essentially need an air traffic control system in place.”

He adds, “How do we separate the drones from each other, and how do we separate the drones from general aviation aircraft? Drones are small. For a pilot who is in a small aircraft, it’s very difficult to see a vehicle that’s that small. It’s the size of a large bird, and it’s out there flying.”

These issues are behind several of the rules the FAA released in June 2016 for what it calls “non-hobbyist small unmanned aircraft (UAS) operations.” The rules cover operational limitations, pilot certification and drone requirements. For example, drones used to transport packages or other property for compensation or hire must weigh less than 55 pounds, including cargo.

In addition, the drone must remain within the operator’s visual line of sight (VLOS) and can be flown only during daylight and twilight. Minimum weather visibility of three miles from the drone’s control station is required. Maximum groundspeed is 100 mph, and maximum altitude is 400 feet. And drones can’t be flown over anyone who’s not participating in the operation.

The new rules are designed to keep drones operating in their own air zone (away from general aviation aircraft) and to make sure operators land their drones if hazards appear. Safety is the watchword.

Separately, President Obama in July signed the FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act of 2016 into law. This legislation addresses the need for “unmanned aircraft systems traffic management,” which the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)is already working on.

“The project being run by NASA is responsible for drone integration and an air traffic management system for drones. It’s an issue of integrating other vehicles in the air, and air-traffic management systems, with drones and building that out,” Ketcham explains. “So the plan is to figure out a way to operate these drones at lower altitudes and have this delivery model—going from point A to point B to deliver a package—take place.”

Environmental issues

Even with an air traffic management system in place, environmental factors such as weather and wildlife will pose some challenges for drone delivery.

“You’re not going to really do anything if it’s snowing or heavy rain,” says John Harra, president of New York City-based Portent Technologies. Portent, which is building a drone to inspect the undersides of bridges, will be up and running in 2017.

Wind can be a problem, too, reducing flying efficiency and putting drones at risk. “The smaller drones can’t take a lot of disturbed air. They keep going off course,” Harra says. Fighting the wind and making course corrections is inefficient and depletes the drone’s batteries faster than flying in calm conditions.

“The winds in the San Francisco Bay Area are often up to 30 miles per hour, coming through the Golden Gate, for instance,” Ketcham says. “If your drone is doing 40 miles per hour, and the wind is 30 miles per hour, you have an issue. What about rain showers? Are these aircraft to fly in the rain? How do they measure and manage their energy? How do they know that they have enough energy so they are not going to fall into San Francisco Bay?”

He adds that such a scenario would result not only in a lost drone but also in an ecological hazard, with the drones’ lithium polymer (LiPo) batteries polluting the waterway.

Wildlife also poses a risk to commercial drone use. Drones in flight can collide with birds (though sense-and-avoid technology aims to prevent such collisions), to the detriment of both bird and drone. And, to defend their territory, birds of prey may attack drones.

“Say you are flying a multi-rotor, inspecting an alpine ski lift, and there’s a pair of nesting eagles. One of the eagles attacks the drone, because it’s in his airspace, his territory. It’s not going to end well for the eagle, it’s not going to end well for the drone and it’s really not going to end well for the little eagle family,” Ketcham says—nor for the drone operator, after word gets out. “Those are the one-offs where people are going to say, ‘Oh, I didn’t see that one coming.’”

Two-legged animals on the ground also could threaten drone deliveries, in a very different way. “You have people out there who overreact to a drone above what they call ‘their property,’” and could resort to shooting at the drone, Harra says. “I think that the government is going to have to state that drones … have same protection as a regular plane that you’re not allowed to shoot down.”

There’s also the possibility of people stealing cargo—grabbing a package attached to a drone’s tether—and inadvertently pulling the drone out of the sky. Delivery drones could be designed to prevent such incidents, incorporating, for example, a quick-release feature that would automatically separate the tether from the drone if someone tugged on the tether; a thief might get away with the package, but at least the drone would be able to fly home.

Then there are the mischief makers who don’t realize how dangerous it is to interfere with a drone in flight. “By the third or fourth beer, somebody wants to help the drone deliver the pizza to them,” Harra says. “People do things without thinking of the implications: I’m pulling this drone down on me.”

Ketcham adds, “Carbon fiber propellers will take your fingers off. The commercial-grade drones, especially, are tough vehicles.”

With so many challenges yet to be addressed, it will take some time for drones to become mainstream delivery vehicles. But with the FAA’s commercial-drone rules now in place, and successful delivery tests occurring in the United States and other countries, drone package delivery is clearly poised to take off.

Kate Bertrand Connolly is a seasoned freelance writer based in the San Francisco Bay Area covering packaging and technology. You can contact her at [email protected].

*****************************************************************************************

Explore other cutting-edge packaging, manufacturing and automation solutions from hundreds of exhibitors at MinnPack 2016 (Sept. 21-22; Minneapolis). Use discount code PDigest16 to get 20% off your conference registration.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like