Revised 2D barcode offers potential in beverage, distribution, ecommerce markets

August 2, 2019

The long-awaited July 2019 revision to DotCode—the barcode symbology adopted for track-and-trace by key manufacturers in the tobacco industry because of its ability to be applied at speeds of more than 1,000 codes per minute—makes one expert wonder if beverage and other high-speed packaging and distribution operations can be far behind in implementing the symbology.

DotCode symbology, revision 4.0—recently ratified by AIM Inc., a trusted global authority on automatic identification and data capture (AIDC) technologies and original publisher of many of the world’s dominant barcode specifications—has been adopted by global standards organization GS1 in a rare mid-year GS1 General Specifications update.

Little-known and previously unhearalded, the potentially revolutionary public-domain DotCode symbology is a two-dimensional (2D) matrix barcode “language” designed by Andy Longacre, Ph.D., and originally published in 2009 by AIM. A distinguishing characteristic of DotCode is its discrete dot pattern that accommodates high-speed and other marking applications where a precise alignment or connection of individual dots or cells may be problematic.

The revised DotCode specification defines expanded symbology-specific print quality assessment (verification) parameters based on a more granular scale (1/10 of a point) to conform with the current SC31/WG1 international committee work to similarly revise ISO/IEC 15415, the standard covering 2D barcode print quality assessment and grading.

Most importantly, the updated specification defines a fundamental encoding improvement based on extensive new testing of the original encoder algorithm and real-world experience in printing and reading DotCode in anticounterfeit and traceability implementations in the European tobacco industry over the past several years.

International Symbology Specification—DotCode (Rev. 4.0) and associated encoding and mask scoring source code files are available for purchase from AIM at www.aimglobal.org. A podcast on this subject is also available on the AIM website.

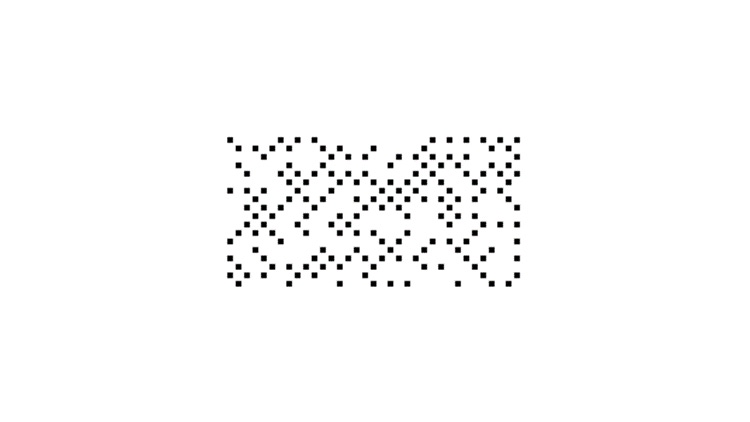

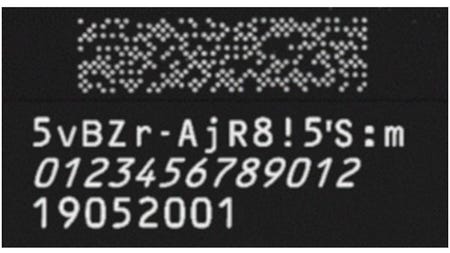

GS1 DotCode encoding a unit packUnique Identifier (upUI) comprised of the new GS1 Application Identifier AI(235) for Third-Party Controlled, Serialized Extension of GTIN (TPX), followed by AI(01) Global Trade Item Number (GTIN), and AI(8008) Time Stamp to YYMMDDhh precision.

DotCode dot array is 63 x 16. Stipulated minimum dot size (X-dimension) is 0.015 inch.

The array dimensions are therefore 0.945 x 0.24 inches PLUS the required 3X Quiet Zone on all four sides for a total symbol area of 1.035 x 0.33 inches. (Image has been enlarged so you can see it better.)

Encodation: 2355vBZr-AjR8!5'S:m0101234567890128800819052001

Scanner output: ]J12355vBZr-AjR8!5'S:m 0101234567890128800819052001

where “]J1” is the required ISO/IEC Symbology Identifier; is the required Group Separator character that delimits the end of the TPX data from the AI(01) application Identifier preceding the GTIN. NO separator character is used between the fixed-length 14-digit GTIN and the AI(8008) Application Identifier.

NOTE: The TPX is comprised of any of the 82 characters in the ISO/IEC 646 character set, including punctuation and other special characters.

Graphic by GW4, compliments of GS1; printed by Domino.

Firmware requirements

It is rare (but not unprecedented) for any AIM or ISO/IEC-standardized barcode symbology specification to be revised in a way that is not backwardly compatible with earlier versions. In this case, the AIM Technical Symbology Committee (TSC) determined that a simple but fundamental change to the symbology encoding algorithm was warranted to prevent the occurrence of rare but seriously flawed symbol patterns. This means printer firmware and barcode design software based on any DotCode specification prior to version 4.0 must be updated.

As for the installed base of barcode scanners/decoders that already support DotCode, the brilliant solution devised by the TSC team—elegant in its simplicity—means that no change to the decoding algorithm is needed. DotCode symbols already in circulation that were (and those which for some transition period still will be) produced using “legacy” software are just as scannable as they always were. And as the DotCode revision notice makes clear, “existing readers can [also] decode symbols generated using the revised encoding method” without any modification or loss in performance.

Speed benefits

Unlike any linear or other 2D barcode symbology, DotCode was envisioned and engineered from the outset to be reliably printable by high-speed marking technologies such as continuous inkjet (CIJ) and laser ablation. These coding and marking processes, when operated at very high speeds, can be far less accurate than at slower speeds.

What is very high speed? Bottling lines for soft drinks, water and other high-volume consumer beverages can exceed 1,000 bottles (or cans) per minute. And in cigarette manufacturing, line speeds are routinely benchmarked at 1,000+ packs per minute.

In fact, the need for a robust and economical-to-apply machine-readable barcode data carrier—encoding a unique, serialized track-and-trace/anticounterfeit identifier applied at very high speed—is perhaps nowhere more urgent than in the global tobacco industry. The European Union is taking the lead.

Protecting public health is a principal concern; but so is criminal activity and lost tax revenue. Thus motivated, the World Health Organization adopted the “WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control” (WHO FCTC) and the European Parliament promulgated Directive 2014/40/EU, both of which are intended to “eliminate illicit trade in tobacco products” in the words of a GS1 document on the subject. More recently the European Commission published Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/574 on technical standards for the establishment and operation of a traceability system for tobacco products.

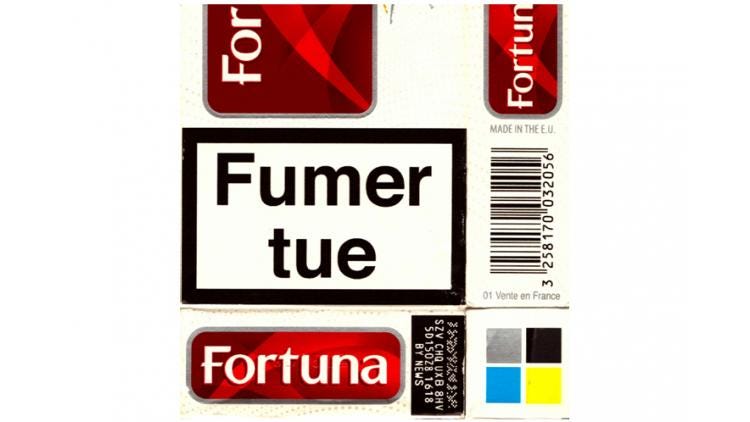

DotCode encoding a unique 12-character alphanumeric code: SZVCHQUXB8HV

Partial front, side and bottom panel of a pack of cigarettes manufactured for the French market prior to 2019 during initial market testing of DotCode laser ablation printing technology. The mandatory black box warning is translated “Smoking Kills.” Graphic by George Wright IV

GS1, the global standards organization that administers the EAN/UPC (GS1) barcode system and the GS1 Gen2 Electronic Product Code (EPC) Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) system in more than 100 countries worldwide, is at the forefront of the development of the globally standardized (or at least broadly interoperable) approach to address this tobacco coding and marking application.

DotCode is the symbology specifically designed for such an application. As GS1 said in October 2016, in General Specification Change Notification GSCN 16-160, High Speed Barcode Printing (HSBP) Solution, “Without a new barcode standard, GS1 members producing tobacco in high volumes declare that they would be unable to comply with the…WHO FCTC…and [European Parliament] Directive 2014/40/EU.”

Far-sighted GS1 Global Office staff, dedicated committee members from dozens of GS1 member organizations (countries) and a variety of supply chain sectors, and visionary AIDC experts understood well before 2016 that DotCode was the robust 2D symbology uniquely suited for printing at very high speeds. The requirements set out in (EU) 2018/574 are based in considerable measure on the years of work and significant contributions from these stakeholders.

Among the updates included in the July 2019 revision to the GS1 General Specifications, support for the tobacco traceability application and the addition of GS1 DotCode are the most significant. (GS1 DotCode is the name assigned by GS1 to the DotCode symbology when the encoded data is structured according to GS1 syntax.) The global GS1 system is built on just a small subset of the many AIM and ISO/IEC-standardized linear and 2D barcode languages; to have another symbology added to the GS1 group is rare and speaks to the demonstrable advantages and potential of the new symbology.

As with all other GS1 symbologies, GS1 DotCode is designated for use at specific packaging levels within a supply chain. Moreover, the use of GS1 DotCode within the GS1 system is further restricted—at least for now—to one specific application: the marking of tobacco unit packs for compliance with EU 2018/574. See section 2.1.14 in the new GS1 General Specifications for details.

Potential new markets?

There is, as yet, no other application defined for GS1 DotCode. But can wine and spirits be far behind? And other applications within the GS1 sphere may be ripe for GS1 DotCode now that it is established within the GS1 system.

According to Scott Gray, solutions architect at GS1 Global Office, “With the ratification of the revised DotCode specification by AIM and the forthcoming release of updated printing systems, readers and verifiers to support the new standard, GS1 is looking forward to conducting additional empirical testing to determine exactly where DotCode may offer an advantage over other GS1 symbologies.”

Another GS1 application Longacre and others originally expected could benefit from the use of GS1 DotCode is “large dot” inkjet printing of case-level GTINs (Global Trade Item Numbers), serialized-GTINs and Serialized Shipping Container Codes (SSCC) directly onto corrugated or other packaging. More recently, the idea has been raised that the edges or ends of dimensional lumber might be directly marked with DotCode—and very effectively read—where linear and other 2D barcode have been less successful.

However, the DotCode symbology does not just support GS1 applications. Although DotCode is optimized for GS1 applications in a way that most other symbologies are not (with the exception of GS1 DataBar), DotCode is a robust, public-domain 2D matrix symbology that is increasingly supported by barcode printer and scanner manufacturers and by barcode label design and other software. Applications outside the GS1 system could potentially benefit from using DotCode, including proprietary applications within an enterprise—consider high-volume ecommerce and other high-speed sortation applications; or in other major supply chains with established non-GS1-based machine-readable marking requirements—including perhaps direct part marking (DPM) and dot peen marking in particular.

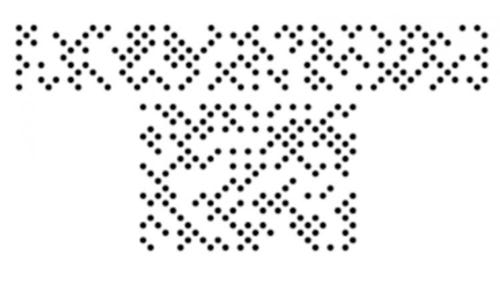

Another feature of DotCode not found in any other mainstream 2D matrix symbology is the flexibility of its shape. DotCode is printed or marked in an array that can be nearly square or more ribbon-like, that is, short in one axis and long in the other (see image below).

GS1 DotCode: Two representative DotCode symbols, each encoding the same GS1 Global Trade Item Number, expiration date and lot number message "(01)00012345678905(17)201231(10)ABC123456", first in a 9-row format and then a 2:3 H:W aspect ratio. The parentheses are used in the human-readable interpretation (space and the application standard permitting) but never encoded, per the requirements for GS1-formatted data. Graphic by GW4, compliments of AIM Inc.

Encodation: 01000123456789051720123110ABC123456

Scanner output: ]J101000123456789051720123110ABC123456

where “]J1” is the required ISO/IEC Symbology Identifier.

With its unique discrete dot design with no connected dots and inherent tolerance of relatively poor-quality printing while maintaining robust “scannability,” DotCode may one day prove to be one of the significant contributions of the early 21st century to the field of automatic identification and data capture technology.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

MinnPack 2019 (Oct. 23-24; Minneapolis) is where serious packaging professionals find technologies, education and connections needed to thrive in today’s advanced manufacturing community. See solutions in labeling, food packaging, package design and beyond. Attend free expert-led sessions at multiple theaters around the expo.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like