Controlling allergens and contamination on food packaging machinery

June 10, 2015

Food packaging equipment professionals are best positioned to safely and effectively design, configure or specify food packaging equipment when they understand the risks of “allergens and contamination” on packaged food safety. Equipment engineers and stakeholders are well advised to collaborate with food safety and quality managers in the quest to control hazards and provide safe products to consumers.

There is an abundance of literature in the public domain relating to the subjects of allergens, contaminants and cross-contamination. Allergens have the potential to trigger abnormally vigorous immune system reactions in hypersensitive individuals and those with compromised immune systems. They, and others who fall into specific risk profiles, may encounter serious harm when exposed to substances which evoke severe bodily reactions such as anaphylaxis, which can lead to serious injury or death if not treated quickly and effectively.

Categories and types of allergens (comestible and non-comestible materials, foods and ingredients) are contained and described within various lists and schedules depending upon the entity or agency responsible for compiling same. The FDA publishes allergen-related information and guidance on its website. The links below represent examples of guidance found on the FDA website:

The Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 (click here to read the FDA’s Q&A on FALCA) applies to all foods whose labeling is regulated by FDA, both domestic and imported. Allergen and sensitive ingredient lists compiled by other organizations or agencies may include items and substances demonstrated or suspected to have historically caused reactions in or to humans.

While the list of allergens is somewhat limited, the term “contaminant” in relation to food, packaged or otherwise, can have broad interpretation. A contaminant in the context of packaged or mechanically handled food may be defined as a substance, component, item or material that is not wanted, expected, specified or typically and necessarily occurring within the product and process. Contaminants may or may not affect the safety, salability, suitability, merchantability and quality of food products. Therefore, it is incumbent upon all members of any supply chain to fully understand types and risk levels of contamination. Contamination may occur from components in foods and ingredients or can be introduced into the packaged food anywhere along the manufacturing and supply chain. Allergens may be considered contaminants when they are unexpected, unlabeled or not suitably controlled.

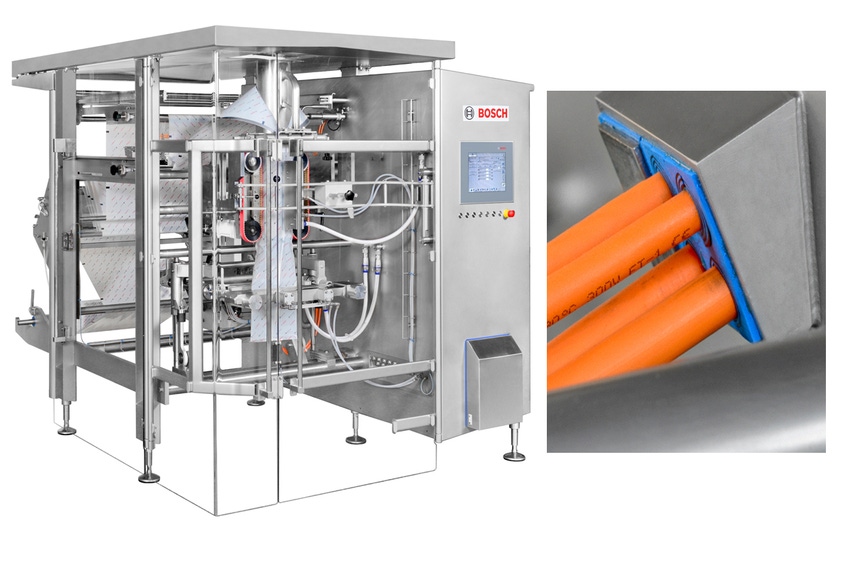

Cross-contamination is the occurrence or reasonable expectation for occurrence of contamination due to (mis) handling, use, environment, ineffective sanitation, shared equipment and changeover or unsuitable equipment or process design. Practically speaking, users of comestible ingredients and food contact packaging materials are applying current best practices when they consider equipment used to convert or process multiple products as affirmatively cross-contaminated in the absence of a written plan and certification to assure freedom from such contamination. Naturally, in order to create and apply an effective changeover and sanitation program, the equipment hardware must have been designed to be fully and effectively cleansed of all traces of components from prior production and be capable of being contacted with safe, approved and effective sanitizing agents.

Food ingredient, process and packaging scientists and engineers are responsible for specifying, testing, acquiring and creating safe food systems for release to consumers. It is difficult, if not impossible, for those functions, as well as quality professionals, to insure the delivery of safe products to consumers if the processing, handing and packaging equipment is not designed, configured, maintained and sanitized to effectively control contaminants and allergens.

Food safety training is critical

Food professionals undergo HACCP and other food safety-related training, which is likely to enhance their awareness of risks, mitigations and related best practices. Many of the same food safety-related precepts applying to food product and package developers are also relevant to those who design, sell, purchase, configure, install, use, clean, sanitize and approve food and food-related handling and packaging equipment. Persons involved in the design, purchase and integration of food processing, handling and packaging equipment are well advised to take a food safety program training course sponsored or presented by an appropriate, accredited organization. These courses include and discuss generalities of equipment, sanitation, use, allergens, contamination, documentation and related food safety content intended to inform participants of industry standards, risks, expectations, controls and mitigations.

Multiple accredited and experienced organizations maintain and supply safe and suitable equipment design and handling information to equipment designers, manufacturers, converters, sellers and purchasers of food handing and packaging-related equipment.

Large, sophisticated users of processing and packaging equipment maintain internal design standards which they provide to potential suppliers.

Independent, accredited organizations and foundations such as NSF International, 3A-SSI, European Hygienic Equipment Design Group (EHEDG) and others are equipped to assess usage situations and patterns, and to determine basic and special needs relating to design standards, expectations, current good manufacturing practices in each industry and best practices as defined in state-of-the-art food safety programs.

Next: Important self-help checklist questions to pursue in advance of design, purchase and factory acceptance testing (FAT).

Clean-in-Place (CIP) systems like this are a common sight in bottling operations. Photo courtesy Federal Mfg Co.

Important lines of questioning to pursue

In general, professionals responsible for design, purchase, integration and use of packaging and related equipment should understand how their equipment might be compromised to facilitate contamination of consumer foods. Basic considerations, understandings and evaluations include:

1. In the case of multi-product applications, determining whether the equipment is suitable and designed for use with all of the food items and categories that the owner/operator intends to convert.

Limitations must be clearly described in accompanying manuals, customer sale contracts and, when necessary, warning placards permanently attached to the machinery.

2. Understanding equipment design features intended to inhibit contamination.

Is the hardware all stainless steel or equivalent non-porous food-approved materials, designed to inhibit corrosion, fragmenting, fatigue, cracking or otherwise degrading?

Are all conduits, conveyances and compartments effectively sealed using materials certified for the intended food use?

Is it free from recesses and crevices which may intake and retain liquids or powders that will ultimately become microbially contaminated and then unknowingly “dispensed” into future packaged food?

3. Can the equipment be effectively cleaned and sanitized to eliminate all traces of matter, internally and externally?

Is it intended for Clean-in-Place (CIP), Clean-Out-of-Place (COP), immersion and reasonable changeover or has it been designed for a “dry brush-down” without wet wash, sanitizing chemicals or post-sanitation swabbing and microbiological testing?

If not, what secondary steps are implemented to insure that allergens and contaminants have not invaded or are residing in, on or near the equipment?

Are all components and accessories designed to withstand water pressure, sanitizing and cleaning chemicals, abrasion and normal “abuse”?

Have the maintenance and repair manuals been customized to include language and procedures which allow, assist and effectively describe what materials, parts or systems to inspect, evaluate, adjust or replace in order to maintain the integrity of the equipment process safety designs?

Are all mandatory procedures, limitations and prohibitions clearly and effectively described in the accompanying literature and in the PLC program(s) in order to avoid customer and service technician errors, omissions and misuse?

4. Is the customer’s organization set up so that the equipment engineers have an ongoing dialogue with safety, regulatory and production professionals (internal or external) regarding equipment use, design, sanitation and the risks of allergenic, microbial, chemical and physical contamination?

Is all equipment included in the HACCP risk assessment? Is an equipment engineer on the HACCP evaluation team?

Has the equipment sanitation and changeover process undergone full HACCP analysis?

5. Once installed, is the equipment and the process it supports likely to induce or support cross-contamination or, alternately, restrict and control it?

6. What credentials are required for the inspectors and technicians who will challenge and validate the cleanliness, sensory neutrality and environmental suitability of the equipment following a changeover and before certifying the equipment “production-ready”?

Can the regulatory director sign the client cross-contamination certificate without fear or concern that it is incomplete or inaccurate?

7. Do you validate or audit your food equipment safety processes using internal or consulting inspection or by reviewing expert protocols which dovetail with current safety program expectations?

Further cautions

Labeling the “sell unit”, or consumer purchasable, with the phrase “manufactured in a facility which contains or processes (one or more allergens or other sensitive ingredients)” does not represent a replacement for best food safety preemptory practices, including proper equipment design, procurement, sanitation, maintenance and validation.

These subjects, like all precepts of food and packaging safety, can seem overwhelming and onerous. Under the Food Safety Modernization Act, each manufacturer, supplier or vendor supporting a food-related supply chain is expected to create and implement processes using safe and suitable materials and equipment which effectively insure the safety of the intended food product(s). In the event of an incident which results in contaminated items reaching distribution, every aspect of your process will be exposed to the scrutiny of the FDA, other regulators and safety experts.

Safety within each function in the food industry requires understanding, knowledge, commitment, execution and validation. Once the knowledge relating to allergens and contaminants has been acquired by the involved project managers on the “equipment side”, the next step is effective and honest collaboration with the safety, regulatory and production champions. Once the process is managed, executed, validated effectively and documented in a written process manual, a template exists for future equipment-based initiatives.

Best practices suggest that clients do business with equipment vendors who are similarly trained and aware of food component and system risks. Better yet, inspect your existing equipment, inspect surfaces and components and ask yourself “would I eat or drink product that contacted these surfaces?”

If the answer is “no” or if you even hesitate when thinking about it, you may need to revisit the requirements for your equipment design or process. Think practically second, think safety first!

Gary Kestenbaum has 40 years’ experience in the food and packaging industries, six as a supplier with National Starch, 18 as a product developer with General/Kraft Foods and 15 as a packaging engineer and developer with Kraft. In his current position as Senior Food Packaging Safety Consultant with EHA Consulting Group, Kestenbaum provides guidance on packaging safety and suitability-related projects for raw material manufacturers, converters and associated supporting professionals. He can be reached at [email protected] or 410-484-9133. The website is www.ehagroup.com.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like