Smarter, smaller, simpler: What’s ahead for robots in packaging?

February 14, 2018

Robots were hot in 2017 and they’ll be hotter still in 2018. It was impossible to turn around without seeing a story about them. Often it was about how robots and artificial intelligence were going to put everyone out of work and that the world would end. Some of the more extreme claimed that robots were conspiring to kill us all. Many of these articles were written by people who know little about robots to be read by people who know even less.

Take a deep breath and relax. It hasn’t happened and won’t in our lifetimes. Robots are a solution, not a problem. As our economy and manufacturing scream past top gear into overdrive, packagers at consumer packaged goods companies and everyone else have a problem finding enough people to staff their plants. The people they have already work too hard and have trouble keeping up with production demands. Robots will help pick up a lot of the slack.

Here are seven areas where we continue to see advancements in robotics:

1. Robomachines

Robots have come a long way. 25 years ago, they were a rarity in packaging, mainly doing heavy lift, repetitive jobs like palletizing or specialized tasks. Today, it is the rare plant that doesn’t have at least a few robots doing jobs—like loading cartons—that used to be done by special-purpose mechanisms.

Remember word processors? Word processing was all they could do. If you needed to do a budget, you needed a separate machine for number crunching. Then came the personal computer. The PC could do word processing, number crunching and much more.

A lot of packaging machinery is like the word processor. It is custom built to do a specific job. It does it well but can’t do much else. When the job changes, the only solution may be to replace the machine. If it can be reused, it costs time and money to modify it. A pick-and-place mechanism does a good job loading a specific product into a specific carton. When the product or carton become obsolete, it’s hard to repurpose and may wind up as scrap. It is even harder to reconfigure a bottle orienter into a bottle capper. They are self-contained and highly flexible.

But with robotics, when the carton loading or the bottle orienting is no longer needed, the robot can be dismounted and used elsewhere. Robots have long been incorporated into packaging machines. More and more, we are seeing them become the packaging machine itself.

Photo courtesy of XPAK USA.

This case erection, packing and closing machine by XPAK USA is a good example. Knocked-down case blanks are stored in a magazine near the robot. The robot grabs a case with an articulated suction cup gripper and pops it open. It passes the open case over stationary guides to close the bottom flaps, then positions the case for loading. Depending on speed and product, the same robot can also load the case. Once loaded, the robot pushes the case through the top-and-bottom sealer. Along with simplicity, the system offers flexibility. Multiple magazines can stage different case sizes and the robot can erect them at random.

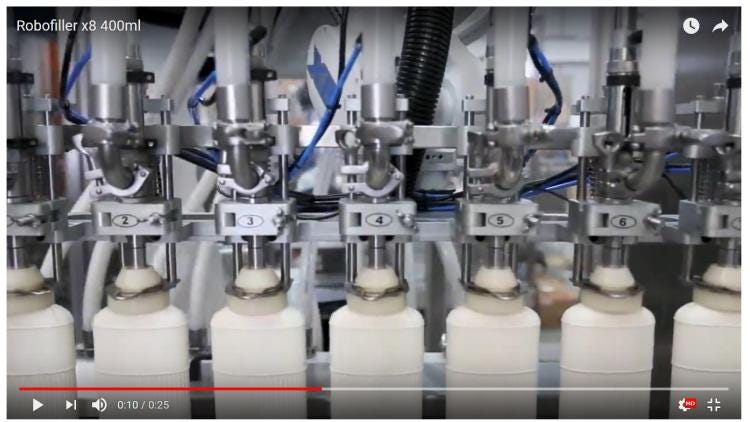

Photo courtesy of FG Industries.

Much of the cost of a bottle filling machine is in the cabinetry, controls and mechanisms. This Robofiller from FG Industries eliminates all that. The filling nozzles are mounted on the arm of an off-the-shelf 6-axis robot. A companion capper mounts capping heads on a similar robot arm.

Changeover is a killer in some plants. Just 10 minutes of daily downtime costs a week of annual production. Robofiller automates changeover. Multiple sets of filling heads can be staged next to the filler. A quick-change coupling allows the filler to automatically place one set in the rack, pick up the next set and keep running almost non-stop with a new product.

NEXT: Vision

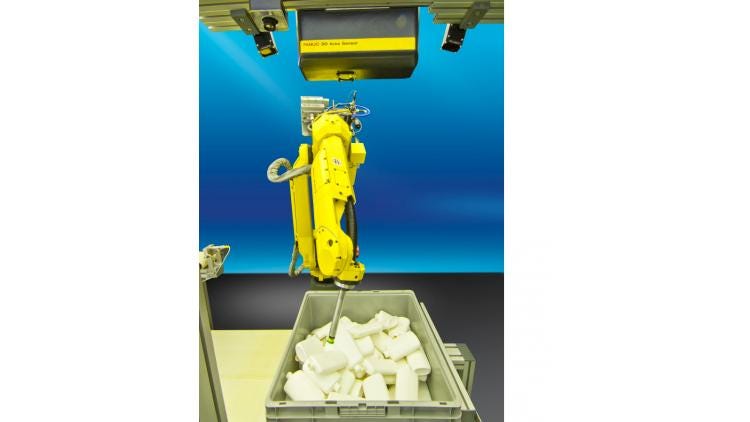

Photo courtesy of Bastian Robotics.

2. Vision

Older robots needed precisely known locations for both picking and placing. Machine vision, or simply “vision,” systems do away with that.

Vision technologies use cameras and software to let the robot “see” what it is doing. They used to be expensive and not very intelligent. Now they are cheap and smart. (You probably have one in your pocket that is smart enough to pick out faces). A vision-guided robot can pick and place parts from and to any location within their reach.

A camera directs this delta robot to pick up a candy on one conveyor and put it in a paper nest on another. Neither candy nor nest is precisely positioned on the moving conveyors.

Until recently virtually all vision systems were two dimensional (2D) and could only work between known, fixed, elevations. Now we have three-dimensional (3D) vision systems. Parts no longer need to be on a flat surface but can be jumbled in a bin, as shown in this video from Fanuc Robotics North America. The camera “sees” the bottle in this example and guides the robot to pick it up. This allows such applications as picking randomly oriented bottles from a bin and setting them upright onto a conveyor. What used to be a purpose-built bottle orienter is now a simple and standard robot, camera and suction cup. They are not fast (yet!) but get faster every day. Even at present speeds, they can free a person from manually placing bottles and let them do something more valuable.

Photo courtesy of Fanuc Robotics North America.

NEXT: Costs

Photo courtesy of Epson.

3. The price is right

Robots used to be expensive and could be hard to justify. Standardization and volume continue to drive costs down. Epson recently introduced its All-In-One SCARA robot which combines robot and controls in a single package. It has a gazillion packaging applications and costs less than $8,000. Other, larger, robots of all types continue to drop in price even while adding capability.

NEXT: End-of-arm tooling / grippers

Photo courtesy of Festo.

4. Getting a grip

One factor contributing to the lower cost is the end-of-arm tooling such as grippers. Custom tooling might cost as much as the robot itself. Design, fabrication and debugging time could delay a hot project. Festo and other companies have developed stock grippers and tooling. Standard, bolt-on, designs shrink costs and lead times. Innovative designs allow reliable handling of irregular or delicate products such as fruits.

NEXT: Collaboration

Photo courtesy of Universal Robots.

5. Works well with others

Traditionally robots and people have not played well together. Robots needed to be caged like dangerous animals to prevent injury to their human colleagues. Collaborative robots have opened up a whole new way of thinking about robots and people. Collaborative robots, such as the one pictured from Universal Robots, can work alongside a person with no guarding in many applications. They do this by using sensors, elastic servo motors and other technologies. The key is that if the human gets close to the robot, the robot stops before any harm is done. This lets the robot act more like a tool assisting the operator and making them more productive.

Tools don’t take people’s jobs, they make them easier and more productive. Think of a carpenter with a handsaw versus a carpenter with power saw.

NEXT: Teaching ease

Photo courtesy of Rethink Robotics.

6. Teaching

As robots get smarter and more capable, they should become harder to program. The opposite is the case. Older robots needed specially trained engineers to program them. Modern robots have simplified programming and graphic HMIs [human-machine interfaces] to make programming accessible to non-specialists. Vision also makes high-precision programming less critical since the robot only needs to go to an approximate position.

An alternative with some robots is teaching. To teach a robot, the operator puts it in learning mode and manually moves it through the task. The cobot Baxter from Rethink Robotics is one example (pictured above). Once complete, the movements are stored in memory. The robot remembers, and can repeat them infinitely. Back in run mode, the robot can repeat the task perfectly every time.

NEXT: Mobility

Photo courtesy of Mobile Industrial Robots (MiR).

7. Moving on…

…or at least moving around. Most industrial robots are mounted in fixed or semi-fixed locations. What if robots could move themselves to where they are needed? Lots of plants have Automated Guided Vehicles but AGVs are like railroads. Very good at moving things but they need tracks (or beacons) to get where they are going. To go somewhere else, they need new tracks or at least additional programming.

AMRs (Autonomous Mobile Robots) are also good at carrying light to heavy loads from place to place, but don’t need tracks. AMRs use an internal map that shows the area, travel paths and any obstructions. The map can be programmed into the AMR or the AMR can move around the area on its own and develop its own map. Like a Roomba but on an industrial scale. (Read more in this recent Packaging Digest article “Mobile robots are adaptable packaging line workers.” When I first saw an AMR at a tradeshow, one of my first thoughts was to mount a collaborative robot. That would turn the AMR into a self-loading and unloading delivery cart. It seems so obvious that I’d be surprised if someone has not already done this as a bootleg project somewhere.

We live in exciting times. Robots, in all their configurations, are going a long way to taking the drudgery off the plant floor. In so doing, they are easing the labor crunch and expanding manufacturing horizons.

Known as the Changeover Wizard, John R. Henry is the owner of Changeover.com, a consulting firm that helps companies find and fix the causes of inefficiencies in their packaging operations. He has written the book, literally, on packaging machinery (www.packmachbook.com) and is the face and personality behind packaging detective KC Boxbottom, the main character in Adventures in Packaging, a popular blog on packagingdigest.com. He can be contacted at [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like